Every time I try to start a blog post (like this one) without first writing an outline, I end up writing unfocused, inefficient copy.

An outline serves as the bones of an article, blog post, or short story. While it’s possible to “fly blind,” it’s not advisable. There’s a reason we’re taught the skill of outlining as early as elementary school.

Every song, no matter the genre, has an underlying structure. These structures serve as the outlines -or blueprints – of music.

Just like starting with an outline has always helped my writing, starting with a song structure has always helped my songwriting, composition, and production.

In this post, we’re going to look at:

- What song structure is and how it works

- Common examples of song structures

- How to do song structure analysis to improve songwriting and production skills

Let’s jump in!

Table of Contents

What is song structure?

Song structure is the “horizontal” arrangement of a song and is a key part of the songwriting process. It is usually sectional, which means it is divided up into parts.

These parts are typically labeled as verse, chorus, bridge, pre-chorus, etc.

Song structure may also be referred to as the “form” of the song, especially in classical music.

Why is song structure important?

Song structure is incredibly important to the songwriting process because it gives the song direction and a sense of purpose. Without song structure, a song may meander and feel aimless.

A great song structure will strike that all-important balance of repetition and new material. This is one of the keys to keeping listeners hooked to the very end of your tune.

The individual building blocks of song structure

Here are the most common song structure elements that you’ll find in popular songs:

Intro

The goal of the introduction is to get your listener’s attention as quickly as possible. Intros can be as long as 16 or 32 bars (or longer in some cases), or as brief as a single beat.

Some intros are instrumental or lyrical, and some songs have no intro whatsoever and go straight into the “meat” of the song.

For example, A Hard Day’s Night by the Beatles starts with a single, ambiguous chord ringing out. The intro of Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen introduces that ubiquitous piano riff before Freddie Mercury’s voice tears into the powerful first verse.

Verse

The verses of a song are typically where the majority of the song’s story is told.

The lyrics in the verses usually paint a picture or tell a narrative of some sort.

The song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen is a great example of a song with verses that tell a story.

The song is about a relationship gone wrong, and each verse Cohen sings adds another layer to the narrative.

This is in direct contrast to the chorus, which simply repeats the title four times.

Verses, like many other elements on this list, are usually in multiples of four bars. For example, each verse in Hallelujah has 16 bars.

Pre-chorus

The pre-chorus is a songwriting device that’s become increasingly popular in recent years. It comes after the verse and helps prepare the listener’s ears for the chorus.

When done well, it can also increase the impact of the chorus by building anticipation or tension. Pre-choruses are usually short, anywhere between 4-8 bars, but there’s no hard and fast rule there.

A great example of this is the pre-chorus of Still into You by Paramore. Listen to how the song drops to only the vocals and palm-muted guitar in the pre-chorus (around the :38 mark):

This makes the high-energy burst into the chorus that much more effective and satisfying.

Chorus

In most modern music, the chorus is really the crux of the song. It’s the section that everything else is building up to; the part you sing at the top of your lungs in the car with the windows down.

The chorus is the part of the song that is meant to be catchy and memorable. No matter the genre, the chorus (or hook as it’s sometimes called) is the part of the song you remember the most.

For that reason, songwriters work hard to make the chorus as “hooky” as possible. This usually means making it catchy, memorable, and easy to sing along to.

Choruses are typically eight or 16 bars long, and they usually contain the song’s title (or a key phrase from the song).

For example, most folks remember Happy by Pharrell by its extremely hooky chorus.

It’s also worth mentioning that some choruses, such as many written by Vampire Weekend, can be entirely instrumental (though this is pretty rare).

Bridge

The bridge is the song’s “twist.” It’s the part of the song that changes things up and provides relief from the repetition of the verse and chorus.

Bridges can be any length, but they are typically eight bars long. For this reason, Paul McCartney (and many other musicians), refer to the bridge as the “middle eight.”

In popular music, you’ll often find bridges between the second and third chorus, as in Super Trouper by Abba.

Listen to how the entire mood changes during the bridge (starting around 2:56). It provides a much-needed moment of change and relief before we go back into that final chorus.

Outro

The outro is the very end of the song, and it’s typically where the song fades out.

Outros can be fading loops of the chorus (as popular in many songs from the ’70s and ’80s) or can introduce brand-new material.

One of my favorite outros of all time comes at the end of Led Zeppelin’s Over the Hills and Far Away.

As the guitar fades out into the distance, it’s supplemented by a gentle pedal steel sound, a timbre we as listeners hadn’t heard in the song until this very moment (around the 4:30 mark).

Interlude

Interludes are songwriting devices that usually come in the form of an instrumental section. They can be as short as four bars or can last for a minute or more.

Interludes can act as intermissions as well. One of my favorite albums is Pet Sounds. The title track is just a series of animal sounds (okay, it’s a little more than that).

But it functions as an interlude between two of the Beach Boys’ most classic tracks: Wouldn’t It Be Nice and You Still Believe in Me.

This break helps increase the song’s energy and keep the listener engaged.

Instrumental solo

An instrumental solo is a section of the song where one or more instruments take center stage and play a series of improvised or pre-written licks.

Solos are usually reserved for the song’s main melody instrument, such as the guitar or keyboard. But they can really be played on any instrument, from the drums to the saxophone.

A great example of an instrumental solo comes in Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb. The song features two guitar solos, one by David Gilmour and one by Roger Waters.

Listen to how each solo enhances the song and takes it to new places.

Genre-specific song structures

Many genres feature song structures and song elements that are exclusive to that genre. For example, Classical music is often organized in the following forms:

- Rondo Form: A-B-A-C-A

- Ternary Form: A-B-A

- Sonata Form: Exposition-Development-Recapitulation

(Feel free to click the links to go to the Wikipedia article for each form and learn more.)

These terms and forms are rarely found outside Classical music.

Jazz, on the other hand, typically features the following unique song elements:

- Head: The main melody of the song, which is usually played at the beginning and end of the song

- Middle chorus: A section that’s similar to the song’s regular chorus, but with a different (potentially improvised or embellished) melody line.

- Vamp: A repeated chord progression that’s usually played at the end of the song while the soloist improvises

As you can see, song structure varies greatly from genre to genre. If you want to evoke a particular style, your best course of action is to become a student of that particular genre.

Do a song structure analysis by breaking down each form, either in your DAW with section markers or simply on a piece of paper.

Understanding the specific song elements and song structures of your favorite genres will help you arrange music that evokes the attributes of those genres.

Let’s get into some real-world forms from popular genres, as well as song structure analysis.

Popular song structures by genre

Now that we’ve looked at the “ingredients” of song structure, let’s take a look at some real-life examples in particular genres.

Popular pop song structures

Pop songs typically follow some variation of this very simple song structure:

Verse – Chorus – Verse – Chorus – Bridge – Chorus

The verse and chorus are usually eight bars each, and the bridge is typically eight or 16 bars. Pop songs may also include an intro or an outro as well.

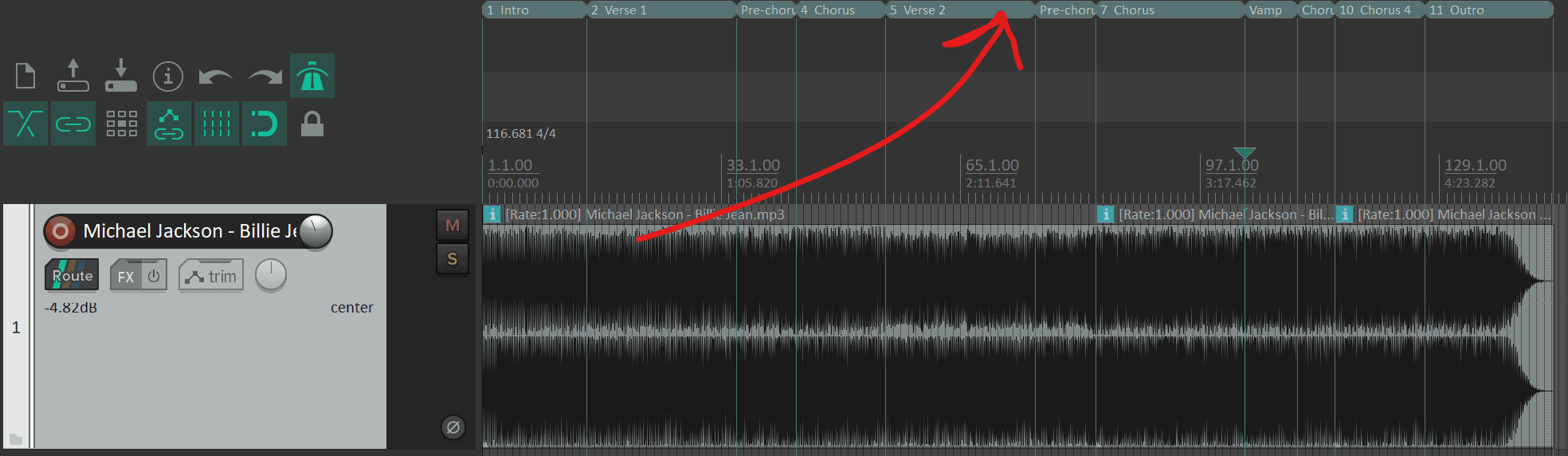

Now, this doesn’t mean the song needs to be formulaic. Michael Jackson uses a variation of this form in Billie Jean while constantly evolving the arrangement and length of each chorus.

He arranges the song in the following way:

- Intro: 12 bars

- Verse 1: 20 bars

- Pre-chorus: 8 bars (“People always told me…”)

- Chorus 1: 12 bars (“Billie Jean is not my lover…”)

- Verse 2: 20 bars

- Pre-chorus: 8 bars

- Chorus 2: 20 bars

- Guitar vamp: 8 bars

- Chorus 3: 4 bars (“she says I am the one…”)

- Chorus 4: 12 bars

- Outro: 16 bars (fade out with various scatting and vamping)

At its core, this is the pop song structure, just highly embellished; each chorus is unique from the last.

Sometimes Michael will sing just part of a chorus, repeat the entire chorus, or come in with a certain phrase (like he does in Chorus 3 after the guitar vamp).

The end result is the perfect blend of both familiarity and surprise.

Billie Jean is such a well-arranged and written song that the genius of this song structure can often be overlooked, but it’s undoubtedly part of what makes it so great.

Now let’s look at a more recent pop song, Can’t Feel My Face by The Weeknd.

Once again, The Weeknd uses the typical pop song structure with a few small twists:

- Intro: 4 bars

- Verse 1: 8 bars

- Pre-chorus: 8 bars (“She told me don’t worry…”)

- Chorus 1: 8 bars (“I can’t feel my face…”)

- Verse 2: 8 bars

- Chorus 2: 16 bars (repeated chorus)

- Bridge: 4 bars

- Pre-chorus: 8 bars

- Break: 1 bar

- Chorus 2: 16 bars (repeated chorus)

- Outro: 4 bars

At first blush, this song seems pretty standard in its use of the pop song structure. Where it keeps things interesting is in all subsequent choruses after the first one.

The chorus is repeated with some extra vocal parts and arrangement elements.

Also, the bridge provides a drastic reduction in the overall busy-ness of the song to prepare our ears for the pre-chorus.

That pre-chorus then unexpectedly extends for one extra measure (the “Break” section) to make that final entrance into the last chorus that much more exciting.

It’s pretty standard stuff, but if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Popular jazz song structures

Jazz songs often have more freedom in their song structure than pop songs. The most common jazz song structures are:

- 12-bar blues

- 32-bar song (AABA)

- 16-bar song

The blues is by far the most popular form in jazz music. In fact, it’s one of the most popular song forms in all of music.

The typical 12-bar blues song form looks like this:

I chord – I chord – I chord – I chord – IV chord – IV chord – I chord – I chord – V chord – IV chord – I chord

So, in the key of C, that would give us the following chord progression:

C – C – C – C – F – F – C – C – G7 – F – C

This song form is so popular because it’s so simple. It’s easy to remember and easy to play.

The only downside is that it can sometimes sound a bit repetitive.

Check out Charlie Parker’s Cool Blues for an example of a jazz tune in the 12-bar blues form:

The other popular song form in jazz is the AABA song form. This song form is 32 bars long and is made up of four sections:

A section – A section – B section – A section

The A sections are usually 8 bars long and the B section is usually 8 or 16 bars long.

This song form was popularized by George Gershwin in songs like Summertime and I Got Rhythm.

All the Things You Are is a great example of a jazz standard in AABA:

It’s a great song form for jazz because it provides enough space for improvisation while still having a familiar song structure.

The last song form we’ll look at is the 16-bar song form. This song form is similar to the AABA song form, but with one less A section:

A section – A section – B section – A section

This song form is popular in jazz because it provides a bit more space for improvisation than the AABA song form.

It’s also popular because it’s a bit shorter, which can be helpful when playing multiple tunes in a set.

So those are three of the most popular song structures in jazz music. Next time you’re listening to jazz, see if you can identify which song form the tune is using.

Popular EDM song structures

EDM song structures are often very similar to pop song structures. The most common song form in EDM is the verse-chorus song form.

This song form is very similar to the verse-chorus song form we looked at in pop music, but with a few small variations.

The typical EDM song form looks like this:

Verse – Chorus – Verse – Chorus – Bridge – Chorus

There difference between EDM and pop, however, is that many EDM songs are entirely instrumental, or feature instrumental “breakdowns.”

This is because they’re often played in clubs to facilitate dancing. Whereas in pop songs you want to hold folks’ attention so they don’t change the radio dial, EDM songs are all about getting people into a “flow state.”

Check out Avicii’s Wake Me Up for an example of a song that uses typical pop song structure with an included instrumental breakdown:

- Intro: 4 bars

- Verse: 16 bars

- Chorus: 16 bars

- Breakdown 1: 12 bars (this introduces the main melody line)

- Breakdown 2: 14 bars (drop happens here; repeat of the main melody line)

- Verse: 16 bars

- Chorus: 16 bars

- Build: 4 bars

- Drop/breakdown/outro: 12 bars

A solid EDM track will be either building tension or releasing tension. The verses and choruses act as building devices that gradually increase the energy for the “drop” or the instrumental breakdown.

How to do song structure analysis

I highly recommend all musicians, composers, producers, and arrangers make a regular habit of song structure analysis.

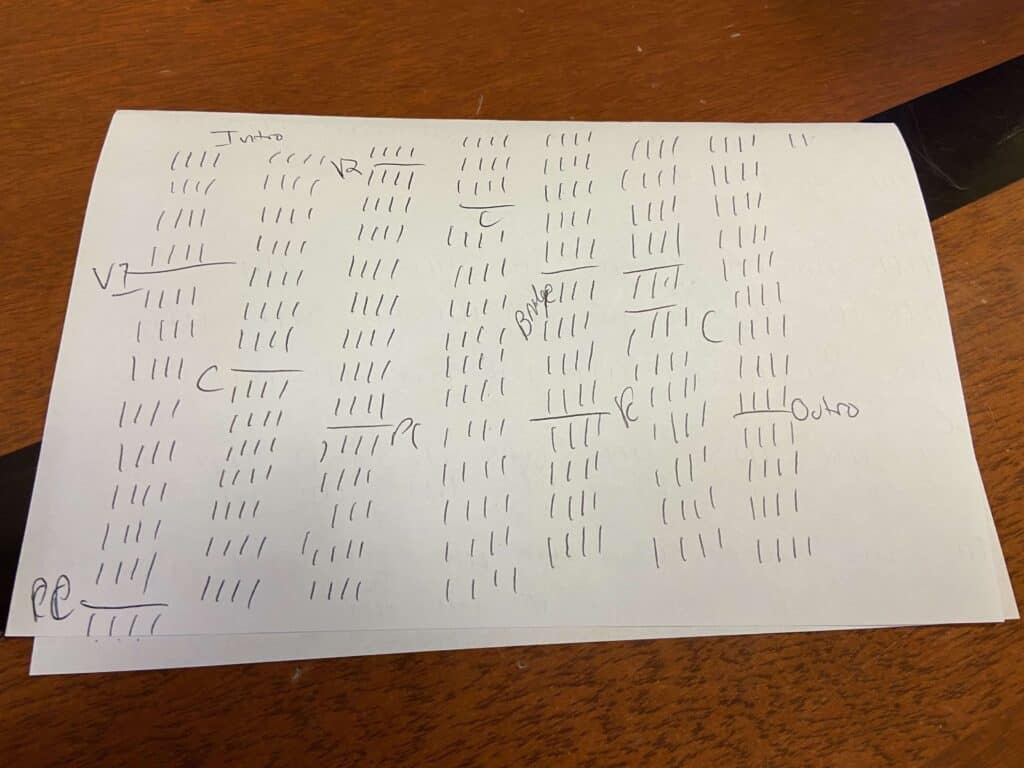

It’s actually quite simple to do this. For this blog post, I simply used a piece of scrap paper and marked each beat with a slash as I listened to the music.

When a section changed, I made sure to quickly notate that with a “C” for chorus or “PC” for pre-chorus.

If you want to be a bit more precise, you can download the MP3 of the track and import it into your DAW.

From there, you can tempo-match the track and create regions or markers to denote each section, as I did here with Billie Jean.

Final thoughts

Setting up your song structure before anything else will save you tons of headaches in your composition, production, or songwriting workflow.

Many genres utilize variants of tried-and-true forms, so there’s no need to reinvent the wheel here.

Studying song structures via song structure analysis will help you get familiar with genre attributes and help you evoke them in your own compositions.

Check out my post on how to write a song for more on the art and science of songwriting. And when you’re ready to start producing your own music, check out my guide on music production.

Thanks for reading!