Everything you need to know about how game composers make money and strategies to boost your game audio career

Gaming (and making music for games) is a very young industry.

It’s been a serious career choice since the early 1980s, and only within the last 7-10 years has it been truly democratized for indies and freelancers. This is thanks in large part to Steam and the explosion of indie games beginning in the late 2000s.

To be clear, there is no set path to build a career in game audio. We’re all kind of figuring it out as we go along.

However, while there is no set path to making a living as a game composer, there are a series of proven strategies that strongly predict success. These are principles that I’ve picked up from over 30 hours of conversation with game audio professionals on my podcast, Composer Code.

Can you make a living as a game composer?

This is the real question. Is it possible, realistically, to meet your monetary needs and make a living solely composing music for games? The answer is a resounding yes. There are professional game composers making a very comfortable living all over the world, and I’ve interviewed many of them.

But like most things in life, it gets more complicated when you dive deeper. Can you make a living exclusively from custom music gigs (probably not)? How does a game composer get paid? What about contracts, royalties, back-end revenue, and passive income? What happens when the gigs dry up?

I’m going to answer all of these questions (and more) in detail in this post, as well as offer a blueprint for making a full-time living in game audio.

It’s important to view this post as a buffet and not as a step-by-step plan. Not everything in this post will appeal or apply to you. Your goals, skills, and time commitment to the craft of video game composition will greatly determine how the following advice works for your career.

That said, this blog post contains (just about) everything I’ve learned myself or picked up from experts on the subject of making money as a game composer. Let’s dive in!

How do game composers get paid?

This may seem like an obvious question to some of you, but it certainly wasn’t obvious to me when I was starting out.

There’s a ton on the internet about the music composition process for games, the technical aspects of production, and even brand-building. But there’s very little on the simple concept of how composers literally get money deposited into their bank account.

Again, Brian Schmidt is killing it in this regard. Definitely check out his posts on the technicalities of how composers get paid here.

Here’s a summary of all the ways composers get paid:

Frontend revenue

This is money that’s deposited directly into a composer’s account either through PayPal or a dedicated payroll platform at the commencement of a custom music project. We are going to talk a lot about the differences between frontend and backend revenue throughout this post, but it’s almost unanimously agreed that composers (or creative professionals in general) should prioritize frontend revenue about everything else, especially as they’re beginning their career.

You can learn more about this topic from my interview with Sebastian Wolff of Materia Collective here.

Milestone revenue

This is money that’s deposited upon the completion or delivering of a certain asset or series of assets in a custom music project, usually around the halfway point. This would also include revenue received upon completion and final delivery or implementation of a project.

For example, a common model is to request 75% of your rate at the commencement of your project (frontend revenue) and 25% upon completion (milestone revenue). This is what I did for Cybarian, my first commissioned soundtrack.

For what it’s worth, some composers, especially established ones, insist on receiving 100% of their rate upfront.

Backend revenue

Backend revenue is an umbrella term that encapsulates any money that composers are paid after the completion of a game or project. Backend revenue numbers are often tied to the success of the game.

Revenue on the backend might include things like a percentage of game sales over a certain amount or even bonus structures based on Metacritic scores (this is a real-life example I heard once).

Taking backend revenue deals at the expense of frontend revenue deals on smaller mid-range or indie games is often not recommended, as many indie games unfortunately fail.

This is the equivalent of a developer saying, “Hey man, spot me this music and I promise I’ll get you back on payday.” You might take that deal from a trusted friend, but coming from some rando developer, it’s a risk.

As Sebastian says in our interview, you may have the next Minecraft on your hands, or you might have a total dud. Remember that 10% of 0 is still 0.

Royalties

Performance Rights Organizations like BMI or ASCAP exist to help composers and artists get paid when their music is performed (mechanical royalties). While this is extremely rare, concerts like Video Games Live or similar tributes to video game soundtracks do pay out a substantial amount in royalties.

Streaming revenue

Despite the hate that Spotify gets from musicians, Sebastian said it made up a substantial chunk of Materia Collective’s revenue (at least at the time of our conversation). Any track that isn’t owned outright by another entity should be on Spotify making money for you.

Steven Melin nets a solid amount of money from his Spotify streams every month. His strategy was to publish piano covers of popular video game music to attract fans of those games and bring awareness to his own brand.

Album sales

While digital downloads aren’t nearly what they used to be, many fans still prefer to support composers by downloading their albums on Bandcamp or even Steam. In addition to digital album downloads, retailers like Bandcamp also allow composers to sell physical merchandise and limited edition collectibles associated with the music.

Licensing

Licensing is such a confusing and catch-all term that it’s almost unhelpful to even talk about it. Nevertheless, it’s an important concept for game composers to understand. Similar to a driver’s license, which grants you temporary permission (until the license expires) to drive a car on public roads, a music license is an allowance a composer gives another entity to utilize their music in certain settings.

Each licensing deal is as loose or strict as the contract written up to enforce it. Some license deals give permission for music to be used in only one setting (a specific game trailer, for example). Other licenses are open-ended and allow the developer to use the music for just about anything while allowing the composer to retain the rights.

Buy-out

A buy-out is the developer’s way of telling the composer, “we want everything.” Meaning, the composer is forfeiting their rights and ownership to the music. The developer is free to do whatever the heck they want with the composer’s work and don’t need to consult them for anything. Also, this typically means composers can’t sell their albums on online distributors or upload them to streaming services.

If composers take buy-out deals, it’s recommended that they charge a very high upfront price to compensate for the potential revenue they’re missing out on in perpetuity. As such, it’s generally best practice for composers to do everything they can do retain the rights to their music.

Passive income

Most composers making a comfortable living in this space utilize some, if not many, streams of passive income. Passive income is such a comprehensive topic that it deserves its own section, which I’ll get into below.

Diversifying your income portfolio as a game composer

I think it’s helpful (and interesting) to understand how composers got paid throughout history.

In the old days, composers made their living through the patronage of an aristocratic family (in the case of Haydn) or employment by the church (J.S. Bach).

Sometimes they were commissioned to write pieces for special events like funerals or weddings for the upper-class social elite.

Nowadays, things are just a touch different. Music pervades every form of media; it’s become a commodity. Robots are learning to compose, for Pete’s sake.

Rather than getting commissioned to write a funeral dirge for an aristocratic matriarch, we’re commissioned by creators (namely, game developers) to write music for their projects.

Unfortunately, living off of these commissions alone, especially when starting out, is almost impossible. This is especially true if you’re a freelancer and not hired as an in-house composer for a AAA game studio.

In the age of the indie dev, when budgets are tight, taxes are high, and health insurance is expensive, composers are forced to think outside the box for ways to keep the lights on.

So what’s the solution? In one phrase: multiple income streams.

Income streams fall into two broad categories: active income and passive income. It’s not uncommon for successful composers to have over 30 income streams from various products, licensing deals, streaming services, clients, and much more.

Let’s explore the difference between passive and active income a bit more.

Passive vs. Active Income for the Game Composer

Passive income is revenue generated in perpetuity requiring minimal to no maintenance from the recipient. I prefer Roberto Blake’s renaming of passive income to “automated” income because there’s nothing passive about passive income.

In fact, it often takes an incredible amount of work. However, once the work is complete, the money comes independent of how much time you spend on it.

Active income is revenue generated from the exchange of goods or services (good ol’ time for dollars). Custom music gigs fall into this category.

Passive income for game composers

Many composers (myself included) recommend that you begin your journey with passive income as opposed to active income (hunting for gigs). This is for a few reasons:

- In the beginning, it’s often very hard to find custom music gigs and you don’t want that to stifle or slow down your progress as a game composer

- Most passive income sources take several months to ramp up, so the sooner you start planting those seeds, the better

I wrote a comprehensive post on several passive income ideas for composers that goes into great detail on how to get started. In the meantime, here’s a tl;dr list of passive income sources for game composers:

- Licensing sites like AudioJungle and Pond5

- Music packs on Unreal Marketplace, Unity Asset Store, or your own site

- Digital courses on sites like Udemy, Thinkific, or Kajabi

- Books or eBooks (Like Steven Melin’s book or Winifred Phillips’ book)

- Membership sites

- YouTube Ad revenue

- Affiliate marketing

Active income (custom music gigs) for game composers

Alright, so let’s talk a bit about the ideal situation: getting commissioned by a developer to write custom music for a game. Truth be told, this is what we all really want. This is where we get to truly exercise our business, creative, and relational skillets.

I think a good way forward is to address some common questions related to custom music gigs.

What does a video game composer do?

This may seem obvious, but it’s an important concept to understand nonetheless. When a developer commissions a composer for game music, what exactly are they paying for?

- They’re paying for clear communication and professional punctuality against deadlines

- They’re paying for you to meet their creative vision

- They’re paying for you to create and deliver raw musical assets in an acceptable format

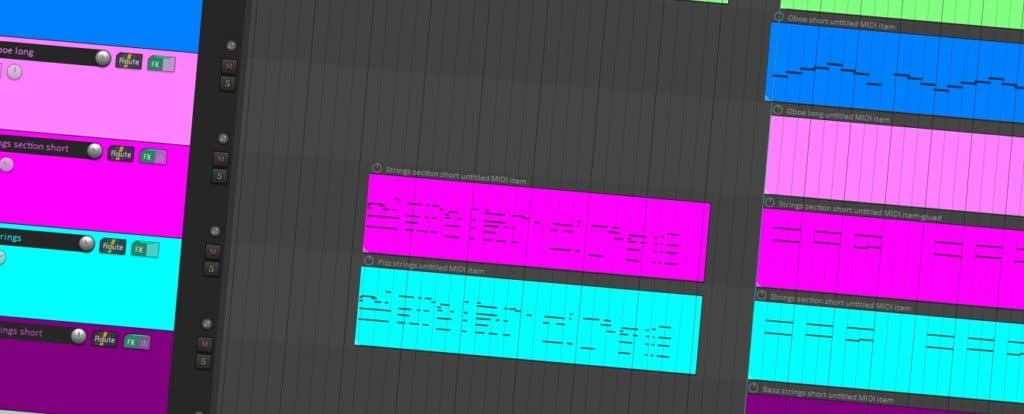

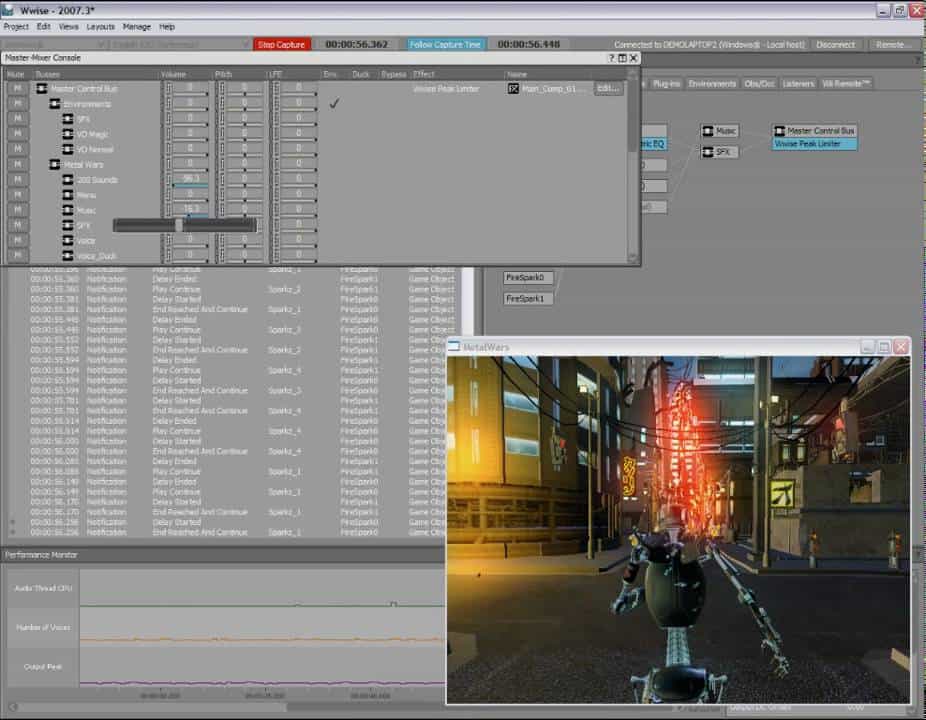

- They’re (sometimes) paying for you to implement those assets using a piece of middleware software like FMOD or Wwise.

- They’re (sometimes) paying you to also create sound effects for the game, though this is a separate skillset and rate altogether.

Sometimes, in the case of AAA or mid-core games, composers may also receive a music budget to record live instruments or orchestras. This is very rare for indie games, however.

How do I find developers to work with?

There are two main ways to market yourself as a game composer: inbound marketing and outbound marketing. Inbound means creating a brand, lead magnet, and funnel that bring clients to you.

You can do this through SEO, brand-building on YouTube, and free music packs that you use to nurture prospects on your email list. Inbound marketing is a highly favorably strategy because of the automated nature of lead generation and the negotiating high ground.

It’s also important to have a robust outbound strategy. It’s not enough to sit around waiting for the phone to ring, you do actually have to go outside your bubble and meet people and seek out their business.

I recommend using the TRACK method for prospecting. It’s a system I wrote up that involves adding radical amounts of value to clients for free in an effort to build trust early.

Networking (or as I like to call it, “relationship-building”) is another skill altogether that requires lots of practice. I wrote up a comprehensive guide on networking for the game composer here. Definitely check that out here before hitting your next meetup.

It comes as no surprise that the best way to find work is through word-of-mouth recommendations or referrals from other composers. I know that’s much easier said than done, and when you’re starting out it can be tough to build the trust necessary to earn those recommendations.

Check out my guide on How to Become a Game Composer for a more comprehensive roadmap if you’re just starting out.

Is it better to be a freelance or employed game composer?

There are certainly pros and cons to being employed or freelancing as a game composer. Many of these depend upon your personality and how you like to work. Some of the benefits of freelancing are:

- Autonomy; you make your own schedule

- Higher earning potential (according to GameSoundCon survey data)

- More flexibility to turn down gigs you don’t like

Some negative aspects of freelancing are:

- Too much freedom can be unhealthy for undisciplined folks

- Not a lot of stability, which makes it a gamble if you have a family

- Frankly, it can get really lonely

Some benefits of working full-time are:

- Income and benefits stability

- Community and the ability to work closely with a team

- A designated working environment away from home

- Structure for undisciplined folks

Some negative aspects of working full-time are:

- Not as much earning potential

- Not as much work flexibility and autonomy

- Can’t say “no” to gigs you don’t like

- The typical drama and trappings of any workplace (dealing with bosses, gossip, etc.)

I had a great conversation on the podcast with Nathan Madsen who’s worked as both a freelance and employed game composer. His insights are pure gold. Check out that conversation here.

How do I set myself apart from the competition?

If you’ve ever set foot in a GDC convention hall or a game composer Facebook group, you know that the composition space is saturated. There are talented composers everywhere prospecting for gigs. It can certainly seem like an impossible task to stand out.

Here are some ways to distinguish yourself from the competition when prospecting for custom music gigs

- Thought leadership – Build a brand on YouTube or your blog around an aspect of game audio you’re passionate about. Nathan Madsen does this in his vlogs, Steven Melin does this on YouTube, and Tom Salta has given Ted Talks on the subject of game audio. This demonstrates to prospective clients that you’re both passionate and knowledgeable about the craft of game composition

- Niching down – Choose one single genre or sub-genre of games and go hard after those developers. If you love 16-bit Sega Genesis-style platformers, make that your sole focus. Note that this isn’t necessarily for everyone. Oftentimes, the joy of being a game composer is the ability to write in several different genres.

- Learn in-demand skills – According to another fascinating blog post by Brian over at GameSoundCon, more than 6 out of 10 game audio job descriptions called for Wwise implementation skills. 31% of job applications called for skills in Reaper (my favorite DAW). A more diverse skillset means a greater likelihood of getting hired. What are the gaps in your skillset, and how can you fill them in to become more of an expert in your craft?

How do I make sure I get paid on time?

Contracts, contracts, contracts. You’re a goober if you start writing a single note of music before a contract is signed. I love the contract templates provided by Hexany Audio here. The password is “gameaudio.”

How much should I charge for custom game music?

The most common amounts that composers charge for music, according to past GameSoundCon survey data, is $100 and $1,000 per minute of music.

A lot of this depends on a few different factors:

- The client’s budget – before blurting out a number, I always start by asking the client, “how much did you want to spend on audio?” and taking it from there. Based on their response, I can tell them how far that money will get them. If they want more music, they can increase the audio budget

- Your experience – to reach some of the dollar figures we quoted above, you’re looking at 3-5 years of experience in the industry. Don’t expect to charge top dollar for at least your first year.

- Your time-to-dollar value – how much is your time worth? Remember that one minute of a piano ballad will take a lot longer than one minute of a sweeping orchestral anthem. Be sure to factor in the time it takes for you to fulfill your client’s vision into your rate

- Your current workload – if you’ve got a full plate of commissions, this means you can afford to ask for higher rates

What’s that you say? You just want a concrete number? Alright, well, I’ll say this: start at $100 per minute of music as a new composer. If the client’s budget is higher, negotiate a higher rate. You can even put in your contract that your rate is normally $500 (or however much) per minute of music, but you’re offering the “indie discount.”

That way, the psychological effect on the developer is to feel like they’re getting a deal and that your music is really worth more. This is helpful for repeat business!

Another idea is to negotiate things like free Steam keys for the completed game (great for giveaways on your blog or YouTube channel!), or backend revenue based on game sales.

As you get more credits under your belt, I would slowly raise your price by 10-15% per gig.

Going full-time as a game composer

Let’s say you’re getting indie gigs here and there and saving up some cash, but you’re still working a day job you hate. How do you transition from a hobbyist or part-time composer to a full-time composer?

Set financial goals

All game composers should have financial goals for their careers, and they need to be SMART (specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, and time-sensitive).

Here are some examples:

Bad goal: Make a living as a game composer in a few years

Good goal: I will be making $50,000 yearly as a freelance game composer by August 1, 2023.

Bad goal: Make some fun money doing sound design

Good goal: I will be making an extra $1,000 per month doing sound design for indie games by January 1, 2021

So what are your goals? Take a moment to think through these questions and write them down (and share them with me, I love talking to you guys).

Find your number

As you’re thinking through how much work you’ll need to meet your goals, you’ll likely run into the realization that it’s not easy to make money as a game composer (shocker).

This, of course, begs the question, “how much money do I really need to live?”

It’s time to find your MVI (minimum viable income): the least amount of money you need to survive. This is a term I’ve pilfered from Fizzle, an incredible podcast, training platform, and blog on building a small business.

Kris Maddigan said he trained himself to live below the poverty line as a young composer. While that may not be necessary (or feasible) for you, there are luxuries we can all cut from our lives to help achieve our ultimate goals.

And once you find your MVI, you now have a clear picture of what needs to happen for you to be able to pay your bills strictly doing game audio.

Three blueprints for transitioning to full-time game composition

Runway approach (least risky)

If you have a day job or a part-time job, it can be daunting to build up a sustainable career while also working 40+ hours.

Just as a runway gives an airplane plenty of space to get off the ground, 6-12 months’ expenses give your business plenty of space to take flight.

This financial runway is the safest bet and an ideal choice for those of us with families. It takes a long time, though.

If you’ve found your MVI, you should be able to extrapolate that out to 6 months of expenses. Oftentimes, this number can take years and years to save, but if you’ve got a family and you’re serious about playing the long game in this industry, I believe this to be the wisest path.

Part-time/bridge job approach (kind of risky)

Sometimes, a part-time job can bridge the gap between your corporate career and game audio career. But on the flip side, how confident are you that you can make up the remaining income to support yourself or your household?

The advantage of taking a bridge job is it can get you to your destination of full-time game audio faster. The downside is that it’s a bit riskier, especially because you need to make up the lost income and your current employer may not be keen on your working part-time. It’s a bonus if you can take a bridge job that’s tangentially related to music, like teaching music lessons or some sort of performance gig.

Cold turkey approach (extremely risky)

If you don’t have a family and your overhead is razor-thin, you might consider just quitting and going for it. It goes without saying that this is by far the riskiest approach of the three, but if you’ve got some savings and are confident you can make the money, who am I to stop you?

An example plan for going full time

Here’s a sample plan for a risk-averse composer transitioning into full-time game audio work:

- Pay off remaining student loan debt

- Begin building a runway of 6 months’ expenses

- Go to every local networking event for game developers/game audio and explore passive income streams like music licensing and streaming

- Develop skills through transcription, analysis, and composition contests

- Focus on creating valuable content on YouTube and personal blog for audience-building

- Quit work and take on a “bridge job” – live gigs, teaching, or freelancing in another area

- Invest more time in composition and slowly wean off of the bridge job

- Create digital products based on audience needs while prospecting a demo reel

- Continue to make inroads with composers and developers at larger conferences like MAGFest, PAX, and GDC.

A lot of these things can be done simultaneously, but even so, this will take five years at least. According to Akash Thakkar (sound designer for HyperLight Drifter) and the data we’ve explored in this post, that’s pretty much right on target.

If you’re anything like me, that can be a pretty depressing prospect. But in the grand scheme of things, five years is nothing. Let’s say you’re 28 right now, and you’ve already got about a year of this stuff under your belt.

In four years, you’ll be 32. To be a working composer by 32 isn’t a bad deal at all. Barring any health issues or acts of God, you’ve got another 30+ working years ahead of you after that.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: it’s crucial to play the long game in this industry.

Next steps

Tony Manfredonia summarized how to be successful in game composition so perfectly in our interview. “Do good work, put yourself out there, and be a great person to work with, and the work will come.”

Everything I’ve said here honestly boils down to that simple concept. I hope that this post provides you with the tactics you need to level up your game composition career and get paid to do something you love.

1 thought on “How to Make Money as a Video Game Composer: The Ultimate Guide [2022]”

Comments are closed.