Proven strategies for becoming a game composer and getting paid to make music for games

**This post has been updated in November 2021**

“How do you become a game composer?”

This is the question I set out to answer three years ago when I first began my podcast, Composer Code. Since then, I’ve interviewed around two dozen video game composers and spent 30+ hours figuring out how to deconstruct (and replicate) their success.

[By the way, I’ve compiled everything I’ve learned into one convenient online course for how to make game music. If you want to bypass this post (and lots of headaches), check it out!]

My podcast guests cover every cross-section of the game composer spectrum. I’ve interviewed indie composers who’d just published their very first OST, composers who’ve been working since the ’90s and have watched the industry transform, and AAA veterans working on multi-million dollar franchises.

This blog post summarizes all the knowledge I’ve gained from my guests and my own experience in the industry.

I have distilled down the fundamentals of becoming a game composer into five pillars, which I’ll unpack in great detail in this guide.

Regardless of where you fall in your game composer journey, how much experience you have, or how long your credits list is, you will learn something valuable from this guide.

I hope that wherever your game composing journey takes you, these insights can offer you just a little more knowledge and help than you would’ve had otherwise. Let’s jump in.

What does a video game composer do?

A video game composer is responsible for writing the music that goes in video games.

However, depending on the scope of the project, size of the development team, and skillset of the composer, composers may also be responsible for other sound-related duties.

For example, after the composer writes the music, it must be arranged, orchestrated, exported, and implemented in the game engine.

All of these disciplines may fall under the composer’s purview, or in the case of larger projects, may be contracted out to others.

Much of that depends on what kind of video game composer you want to be. Are you a pure hobbyist? Indie game lover with a “startup” spirit? Or do you want to join a AAA studio and be a cog in a large machine?

How you think about these questions segues perfectly into our first pillar of becoming a game composer – setting goals.

Pillar #1: Defining Success as a Game Composer

What do you want out of game composition?

Many people I encounter in Facebook groups, on Twitter, or at conferences say some sort of variation of “I want to become a game composer.” You may have said something similar at some point. Perhaps it’s why you’re reading this post right now.

It’s only after interviewing over two dozen game composers over the past three years that I’ve realized that the most helpful response to that statement is: “What do you mean by that?”

In other words (I’m talking to you now, dear reader), what is your definition of success as a game composer? Because wanting to “become a game composer” could mean at least three different things.

“I want to make music that could go into a video game”

This is purely hobbyist music-making, and it’s great. There’s a thriving chiptune community that makes music in this spirit: no game credits, no developers, no implementation, no pressure. Just making music in the spirit of the classic retro games we all know and love.

Maybe this is what you want. Maybe turning music into a career sounds like a total drag to you. There’s no shame in that.

“I want to compose game music as a side hustle”

This is where I fall.

I have a full-time job as a music director, a wife, and two kids. Game music for me is strictly a side hustle, and I love it that way. I can choose what jobs I want to take or reject.

(By the way, I’ve written a comprehensive post on how much video game composers make.)

I can decide who I want to work with, and I don’t need to feel pressure to pay the bills with inconsistent composition gigs.

It’s purely a way to make some extra cash and then funnel that cash back into fun gear and projects like Composer Code. But maybe that’s not enough for you.

“I want to be a full-time game composer”

I would venture a guess this is what most people mean when they say they want to be a game composer.

Full-time game composition is a hard road; it’s the hike up Mt. Everest. But once you get to that summit and plant your flag, it’s all worth it.

But even this requires more explanation. Do you want to be a freelancer or have the security of full-time employment at a development firm or studio?

Freelance composer vs. in-house composer: which to choose?

Are you the kind of person who wants to make your own hours, work from the comfort of your home studio, and stay highly disciplined in your weekly tasks?

Or, are you the kind of person that thrives off the stability and accountability of a 9-to-5 job?

How you answer these questions (and others) will likely determine your ideal goals as a game composer.

I originally titled this section “indie game composer vs. AAA composer.” But the more I thought about it, the more I realized the false dichotomy of that statement.

The spectrum of indie games vs. “mid-core” games (whatever that means) vs. AAA games has become so blurred that it’s almost pointless to use these categories anymore.

For example, my first commissioned game soundtrack was for a 16-bit side-scrolling platformer. The developers had a minimal budget, and the soundtrack was only ten minutes of music.

Austin Wintory wrote the score for Journey (which was nominated for a Grammy) and featured some of the most captivating modern orchestral music in a piece of media.

Are we both “indie game composers”? Technically, yes. But only like how Elon Musk and I are both men. That’s about where our similarities end.

There are lots of AAA composers that work exclusively on a freelance basis (like Tom Salta and Jason Graves) and a lot of indie game composers that work in-house.

Let’s take a look at these differences together and see which path is the right one for you.

Salary differences

So how much money do freelance composers make vs. in-house composers?

Well, pricing art has never come easy to humans. The salary disparities in game audio are wide. Very wide.

Thankfully, we have Brian Schmidt and the folks at GameSoundCon doing the excellent work of gathering this data and demystifying these statistics.

Nearly 400 working composers submitted their information in an anonymous survey to complete the GameSoundCon Game Audio Industry survey.

Freelance game audio professionals reported lower income on average ($63,548 per year) but seemed to have higher earning potential than salaried composers (read the full report here).

That signals to me that, while salaried employees have stability, structure, and potentially more corporate benefits like employee-owned healthcare, freelancers can make more cash.

It makes sense. The essence of freelancing is “you eat what you kill.” Freelancing is attractive to highly ambitious people because your earning power is limited only by your work ethic and your team (should you choose to build one).

Pros and Cons of Freelance vs. Salary

Here are some pros and cons of working as a freelancer versus a salaried composer. I’ve collected these things from my own experience as a working freelancer as well as my guests’ experience (specifically Grant Kirkhope and Nathan Madsen).

| Pros of freelancing | Cons of freelancing |

|---|---|

| Much more room for scalability | No structure; may be difficult for undisciplined people |

| The ability to build a brand with a full team | Lots of time alone; extroverts may get lonely |

| Complete creative control | Riding the “entrepreneurial roller coaster” can be emotionally taxing |

| The ability to be “choosy” with projects | Running a freelance operation requires marketing, accounting, admin work, and more |

| Autonomy with working hours and working location | Income can be feast or famine |

| Pros of salaried work | Cons of salaried work |

|---|---|

| Working closely with the development team and other composers is extremely rewarding | Not a whole lot of room for growth unless you want to be a music/audio director |

| Prospecting is not the responsibility of the composer but the company itself | May need to work on projects you’re not passionate about |

| Benefits like healthcare, 401k contributions, and paid sick leave | Average earning potential is lower |

| Structured and (often, but not always) more stable than freelancing | Not a lot of autonomy concerning work hours and work location |

You can't always control your path

This entire section comes with one big caveat: you often can’t control what happens to you in your career.

When I interview game composers and hear their stories, it’s often a tale of one opportunity that leads to another opportunity that leads to another.

I’m not saying you shouldn’t have a goal and work towards that goal. Knowing what you want out of your game audio career will help you know which opportunities to take and which to turn down.

My point is that, due to factors beyond our control, we can’t always control where we end up in our careers. In an industry as young and scrappy as game audio, sometimes you need to be okay with going along for the ride.

Now that you’ve hopefully thought through your own career goals and which path aligns best with what you want let’s move onto the fun stuff: the actual craft of composition.

Pillar #2: Honing Your Craft

There are lots of disciplines game composers must master if they want to succeed in the industry. You must be able to communicate and collaborate well with development teams, understanding the game dev life cycle, and market yourself and your work.

However, none of this matters if you don’t spend time honing your mastery of composition itself.

No gear, fancy plugins, or industry relationships can replace good ol’ fashioned composition chops.

Learn to steal like an artist

I have “lightbulb moments” all the time on my podcast. A guest will say something about their process or their story that’s so profound, yet so simple, that it blows my mind.

One of my favorite lightbulb moments was with 8-bit Music Theory when he opened my eyes to the power of transcription and imitating our influences:

“The difference between plagiarism and writing a good piece of music is that instead of stealing from one song, you’re stealing from six.” – 8-bit Music Theory

Everything you or I know about making music we’ve consciously or subconsciously picked up from someone else, whether Mozart, the Beatles or Koji Kondo.

And they picked it up from composers before them. For better or worse, we are all walking combinations of our influences.

For a more fleshed-out argument for this indisputable truth, I recommend checking out Steal Like An Artist by Austin Kleon.

Read that book, and you’ll see just how far back the practice of stealing from other creatives goes.

With every song you transcribe and analyze, you assimilate that composer’s vocabulary into your box of tricks (if you’re intentional about your analysis, of course).

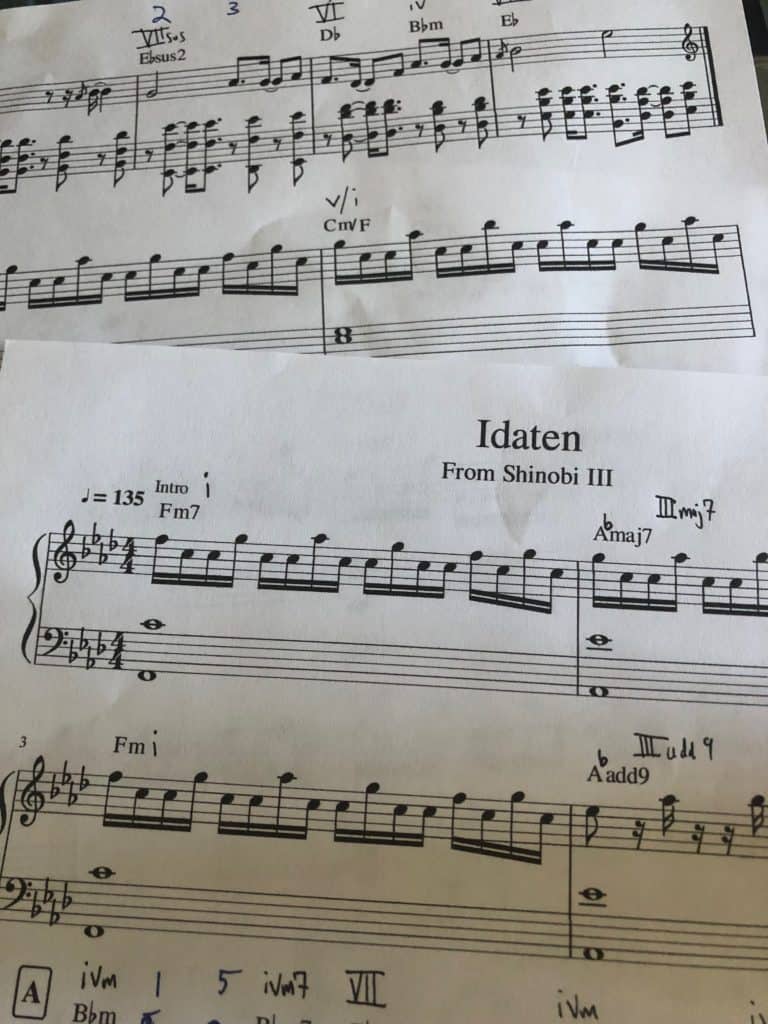

Transcription helps you assimilate musical vocabulary

When the powers at be approached Gordy Haab to write the music for Star Wars: Battlefront (2015), he transcribed and analyzed key sections of John Williams’ original score.

When Kris Maddigan’s childhood buddies asked him to compose music for Cuphead, he had no idea how to write music for big band combos. What did he do? He transcribed a ton of Scott Joplin and big band charts.

Genre-specific cliches are easy to identify through transcription. Need to write a tropical theme for a client’s racing game? Transcribe some Koopa Troopa Beach from Mario Kart 64 and study what makes it sound “beachy.”

Whether you’ve composed two tracks or 200, there is always more to learn through regular transcription.

The spectrum of transcription

When I first discovered the world of transcription, I was kind of a fundamentalist. I thought that if you didn’t notate everything in an actual musical stave, your transcription didn’t count.

Realistically, working composers don’t always have time for that. I learned that myself when I picked up a game soundtrack commission with a tight turnaround.

I’ve since realized transcription is more like a spectrum. There are more “loose” transcriptions and more “rigid” ones.

Here are a few different ways you can transcribe:

- Active listening

- Learning the piece on an instrument

- Cheatsheet

- Leadsheet

- Full score

I wrote a comprehensive guide on how to transcribe music and why transcription is so essential. Check that out as you embark on your transcription journey.

Learn the fundamentals

Michael Jordan went on record saying, “get the fundamentals down, and the level of everything you do will rise.”

Jordan knew that if he focused on mastering the foundational aspects of basketball — dribbling, ball control, shooting, defense, passing — everything else would naturally improve.

The same is true of composition. It seems like you can’t go anywhere online without getting sold a MIDI pack of chord progressions, a plugin that creates a song for you, or “plug and play” melody-generating algorithms.

[Related post: How to Make Game Music: 14 Strategies]

These things aren’t bad and can be very useful in stimulating your imagination. But you won’t get very far in this industry if you don’t have a solid grasp (or better, mastery) of the basics.

Learn the fundamentals of these four areas before you get distracted by the endless minutiae of plugins, production, or high-level theory techniques:

Learn the fundamentals of harmony and melody

Harmony and melody are two sides of the same coin. They inform, enhance, and build upon one another to create the timeless tunes we know and love.

Most VGM tunes are held together by a memorable melody and a harmony that supports it. I wish there were a silver bullet on how to write a great melody, but there simply isn’t.

Here are a few tips to get you started, though:

Understand the basics of theory, including chord tones vs. non-chord tones and functional harmony. You’ll be up-to-speed if you spend a few days going through the excellent free lessons at musictheory.net.

Study, analyze, and transcribe your favorite VGM (read my post on transcription and analysis here).

Choose a scale, mode, or key as a starting point so you’re not overwhelmed by “option anxiety.”

Use the Circle of Fifths as a guide for crafting satisfying harmonies or creating new and exciting ideas.

Singable melodies have a higher likelihood of getting stuck in people’s heads. Try coming up with themes with your voice first before committing them to your compositions.

Whenever possible, figure out your structure first, so you have clear constraints of how much music you need to write.

If you’re not sure what harmony you want underneath a melody, try adding a simple bassline first, then filling out the other notes of the chord later.

Experiment by starting your compositions with different elements. For example, try starting with a progression, a melody, or a rhythm. Usually, the genre or mood will dictate which is most appropriate.

Sometimes a melody works better as a bassline or counter-melody than an actual melody. Experiment by placing your melodic ideas in various octaves.

Use repetition to your advantage while slightly tweaking repeated sections to keep the listener interested.

Learn the fundamentals of arrangement

Arrangement is the difference between a bunch of melodic ideas and a fully-fledged composition. It’s the discipline of fleshing out your melodic and harmonic ideas with actual instruments.

These instruments don’t stand alone but interact with and play off of one another to create an orchestration of the piece (even if orchestral instruments aren’t involved).

[Check out my new post on how to arrange music]

Arrangement, like composition, is something you could spend your entire lifetime learning. That said, here are some tips to get you started:

Layer melodies, harmonies, effects, and sounds in one 8-bar section, and then duplicate out that section to match the desired length of the song. Then, methodically delete or strip away portions to create specific moods or atmospheres.

All rules are made to be broken, but if you find yourself stumped as to where to go next, most songs usually contain some form of the following:

- Melody

- Harmony

- Bass

- Rhythm

- Pad (a droning, atmospheric texture that glues the piece together)

- Counter-melody (a melodic line in a similar register of the melody that plays off the melody)

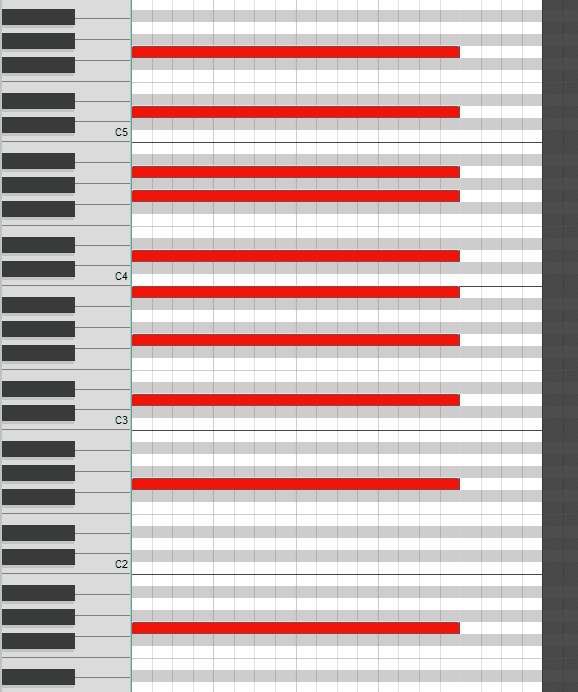

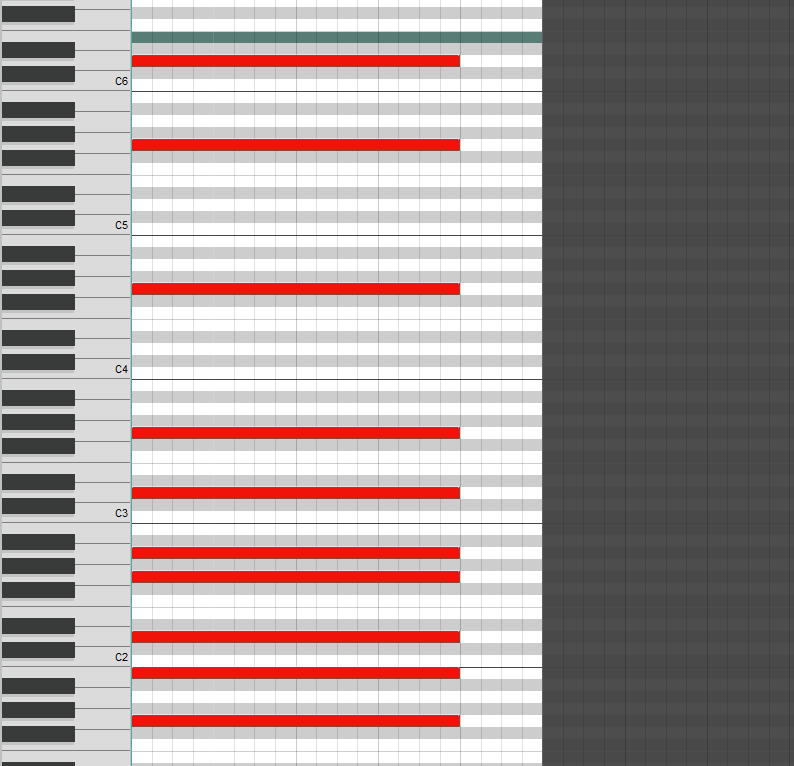

The harmonic series is how sounds occur in nature. Without getting into too much science, a general rule is that low notes clustered together tend to sound muddy, while low notes spread apart sound resonant and pleasing. On the flip side, high notes clustered together are easier to discern, while high notes spread far apart can be jarring or distracting.

On this last point regarding the harmonic series, look at this example voicing of a chord (Gsus2) and click the audio file to hear it:

Gsus2 chord voiced according to harmonic series

Now look/listen to this same Gsus2 chord (screenshot below), but voiced “against” the harmonic series (with more notes clustered in lower registers than higher registers). Sounds a bit muddier, doesn’t it?

Gsus2 voiced “against” harmonic series

Again, using “rules” in art is always dicey. Maybe muddy is what you’re going for. These are just principles that have guided composers for many years.

Learn the fundamentals of production

Production is not scary. I think we make it a lot more complicated than it needs to be. First off, don’t buy expensive mixing plugins. Use the stock mixing plugins that come with your DAW.

I promise you until you master those plugins, investing in more big-ticket plugins is a waste of money, and the average listener will not notice the difference.

Besides, most DAWs like Logic and Ableton (even Reaper) come with very capable plugins. I have even preferred some of these stock plugins over paid ones.

Here are the principles of production that you’ll want to familiarize yourself with:

- Volume balancing (this is like 85% of mixing)

- Automating parameters over time to make the track come “alive”

- Controlling dynamics with compression and limiting

- EQ

- Time-based effects like reverb, delay, and modulation

- Distortion effects like bit crushing, overdrive, and saturation

I don’t want to get into the weeds of production in this blog post (there’s quite a bit to talk about). However, I will refer you to the course that taught me everything I know about production: Audio Mixing Bootcamp by the legendary producer Bobby Owsinski.

He’s also got an Audio Mixing Masterclass, where he opens the kimono on some advanced mixing techniques used by bands like the Beatles and Van Halen.

I would highly recommend investing in a course if you want to learn more about production. Trying to learn to mix and master piecemeal through YouTube videos is going to be confusing and overwhelming.

The good thing about video game music is that, unless you’re utilizing lots of live instruments and players, most VSTs are “pre-mixed” for the most part and don’t require a whole lot of treatment.

You might find yourself doing some light EQ, volume balancing, and automation, but that’s about it (in my experience).

Learn the fundamentals of game development

It’s essential to understand the whole flow of how a game goes from an idea to a reality. This includes having a basic understanding of middleware, game design docs, and how team members communicate and collaborate.

Game jams are the best for this (something I touch on later in this post).

Build a Volume of Work

One of the biggest differentiators of successful composers is that they make creativity a habit.

You must find time to compose every day. You can read this guide and listen to all my podcast episodes and maybe feel like you’re making progress, but until you put it into practice in the nuts and bolts of writing, you won’t move forward.

It can be tempting to wait until a client hires you to start writing music, but a good rule of thumb is always to act like you’re on a gig.

Pretend you’ve got a boss that’s breathing down your neck to produce a certain amount of music per week. Pretend you’re constrained to a fictional creative brief and a client: troll game dev forums, Facebook groups, and game jams for inspiration.

Whatever you do, always be writing.

The Super Marcato Bros do this better than just about anyone I’ve seen. Early in their career, they would take a beloved game soundtrack and write their own full-fledged OST set in that “world.”

The result? A Bandcamp page filled with tons of music to send to prospective clients.

Lest you think this is an isolated case, consider these other examples:

When Garry Schyman was approached to score Destroy All Humans, the developers were looking for a very specific sound: music in the vein of the renowned film composer Bernard Herrmann.

Well, as it just so happens, Garry was a massive fan of Herrmann and already had music in his portfolio written in that style. He sent it over, and next thing you know, the gig is his.

Now, could Garry have still gotten the gig had he not had that music? Maybe. Probably. But the fact that he had already composed a volume of work that he could send over gave him that competitive edge that landed him the commission.

Emmanuel Lagumbay did the same thing with his OST for VentureVerse. They wanted epic fantasy music. Emmanuel just happened to be a Warcraft fan and had already written music in that style. He sent it over, and – you guessed it – he got the gig.

So what music do you like to write? What music do you see a need for among game devs? Find where those two intersect, and start building your volume of work.

Don’t just build solo tracks, either. Building entire albums helps you experiment with theme and variation, create a palette of sounds, and have a robust completed project to showcase on your demo reel.

And make it a habit. Set a time in your calendar to compose. Even if it’s for 30 minutes a day at night when the wife and kids are asleep. Everyone’s got 30 minutes, right?

Perfect your workflow

If your goal is hobbyist composing, you don’t need to worry about workflow. But all professionals know that time is money. The faster you move your art from ideation to creation to production to completion, the more work you can take on.

Paradoxically, this doesn’t mean you should focus on speed. Focus on the proficiency of your art and the frequency of your art. The speed will naturally come.

There are lots of ways you can mentally improve your workflow, like setting deadlines, training yourself to finish songs, and “killing your darlings” early and often when they’re not working.

There are also many ways to technically improve your workflow, like learning keyboard shortcuts, setting up DAW templates, or setting up a palette of sounds early.

I wrote a blog post on perfecting your composition workflow. You can check it out here.

Get involved in GAme Jams

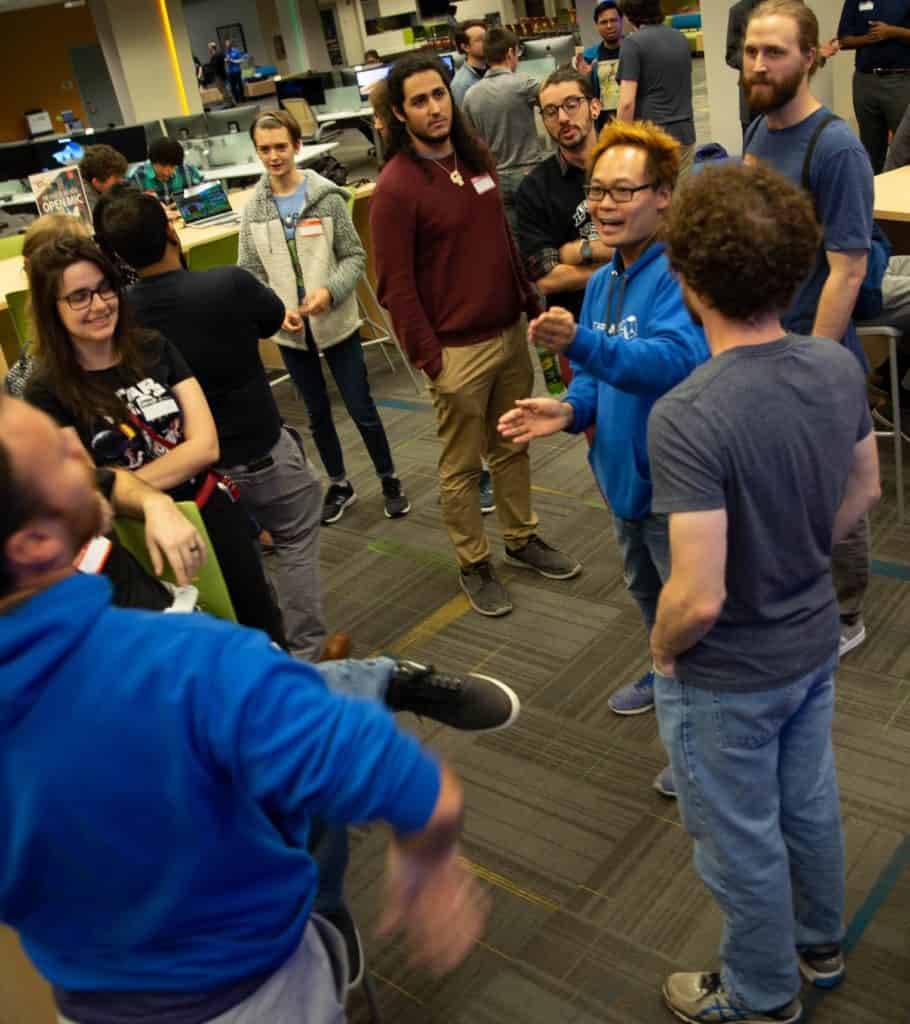

For those of you who aren’t aware, game jams are physical or (as in the case of a global pandemic) digital events where creatives gather to pitch game ideas, form teams, and rapidly create a playable prototype within a specific time frame.

My guest Chase Bethea (Aground composer) told me that game jams were his number one avenue for building relationships in the game audio space.

Now in my experience, it’s possible to meet people at game jams that open up opportunities for paid work. Heck, The Binding of Isaac started as a game jam game, and we all know how that ended.

But I’ve found that there are other equally valuable benefits to regularly participating in game jams.

Benefits of Game Jams

Why join game jams, you might ask? I’ll give you three big reasons:

Before joining the Indie Galactic Space Jam in 2018, I had no idea how the game development process went. I had no idea how programmers, artists, animators, creative directors, and composers worked together to create a finished product.

Up to that point, I had only worked with indie games where I threw music assets over the fence and they magically appeared in the game.

We were fortunate to have Necole, a very experienced creative lead, as our team leader and I learned a ton from her. I learned about the importance of a game design doc (a comprehensive document that serves as the game’s central source of truth for aesthetics, story, graphics, and everything else) and team alignment.

You might think making an extra document containing all this data is kind of overkill for a 48-hour game jam, but I can’t tell you how many miscommunications we had even with the design doc. In fact, one of the programmers spent a whole day working on something unnecessary because he didn’t reference the design doc.

I got to see how artists worked, how 3D modelers transferred assets to our programmers, how our programmers implemented them in Unity, and much more. It was such an educational experience and will absolutely serve you well if you want to make a career working with game developers.

I thought most of my time would be spent with my nose in my DAW writing tracks. I was shocked that about 60% of my time was actual composing and 40% was interfacing and collaborating with the team.

I was constantly talking to our creative lead, our head programmer, and our designers about how my work would help align with theirs. The experience really helped me understand the value in team communication and maintaining a consistent vision with the other developers.

There’s a delicate balance between being an inflexible jerk and a total pushover. I think I strike that pretty well, but I suppose you’ll have to ask past clients to confirm that. 🙂

Our creative lead had a particular vision for the music, but I had some reservations. I expressed my reservations and suggested an alternative (a great formula for compromise), and the end result was something we were both happy with.

Time waits for no one, and neither do game jam judges. One of the best benefits of game jams is that it forces us perfectionistic, noodling, hand-wringing, self-doubting creative types to actually finish something. And that, we did. We won second place, too.

There’s never been a better time to join a digital game jam then during this lock down. Check out some upcoming digital game jams on itch.io.

Pillar #3: Build a foundation of passive income

What is passive income for composers and musicians?

Passive income is revenue generated in perpetuity requiring minimal to no maintenance from the recipient. I prefer YouTuber Roberto Blake’s renaming of passive income to “automated” income because there’s nothing passive about passive income.

In fact, it often takes an incredible amount of work. However, once the work is complete, the money comes independent of how much time you spend on it.

Why should you care about passive income?

Passive income frees you up for other projects

If there’s one thing I learned about business (especially the business of game composition), it’s that the sooner you can separate your time from your earning potential, the better.

Think of it this way. Let’s say you’re able to, by some miracle, land a series of subsequent game composition gigs without any downtime.

Based on your rates and how quickly you work, you deduce that you make about $50 composing. Now, there are only 40 working hours in a week, so if you ever wanted to make more money, you have two options:

- Raise your prices

- Figure out a way to not sleep

The first option works (to an extent). However, not only does it take years of experience to be able to raise your rates significantly, but unless you’re working with mid-core or AAA studios, you will reach a point of diminishing returns. You will hit a threshold where people just aren’t willing to pay what you’re asking.

Now, let’s say you have a series of passive income sources (game music packs, royalties, Spotify streams, etc.) that bring you in an average of $500 per month. Now, you can still raise your prices, but the beauty is that you can afford to turn down certain gigs and concentrate your efforts on other projects.

These projects may be building a team of composers, traveling to an event for networking purposes, or even starting a sample library company like my buddy Steven Melin did.

The point is that passive income frees you up from a perpetual cycle of “time for dollars,” and more time means more bandwidth for making high-level business decisions and working on more profitable projects.

Passive income compounds over time

Passive income takes time, just like compound interest in the stock market. That’s why they say that investing in the market with a small sum is ultimately more lucrative than trying to invest a huge amount later in life. Compound interest needs time to work its magic.

The same is true of passive income. It’s a long tail strategy, meaning reaching your maximum monthly income can take 6-12 months of the market responding to your work.

For this reason, Steven Melin recommended in our very first conversation that composers start by concentrating on passive income sources.

After all, what else are you gonna do while prospecting for gigs and waiting for devs to call you back?

It’s like planting a seed. You’ll want to plant those seeds right at the beginning of the season so they have plenty of time to grow, then work on other tasks around the farm.

Passive income fills in the gaps in dry seasons

The bottom line is that, even if you’re an in-demand composer like Jason Graves, you don’t have a crystal ball. You can’t tell when your next gig is going to come in.

Relying exclusively on custom gigs can be a risky strategy, especially when you’re just starting out.

Passive income ensures you at least have a buffer of reliable income coming in each month.

Freelancing as a game composer is already stressful enough. Anything you can do to lessen the “entrepreneurial roller coaster” (especially if you have a family or people depending on you) is wise.

Practical Passive Income Strategies

Some viable passive income strategies include (but aren’t limited to) the following:

- Licensing your music to marketplaces like AudioJungle or Pond5

- Streaming/download revenue (this is especially viable if you do cover songs that people are already searching for)

- Products (physical or digital) like courses, album artwork, communities and membership sites

- YouTube Ad revenue

- Affiliate marketing (promoting gear, plugins, or brands that you believe in and getting paid a kickback whenever your users click your link to buy)

However, by far the most interesting and productive passive income channel to invest in is creating game music packs for developers.

Game music packs

If you’re an indie developer on a shoestring budget (or no budget at all), hiring a composer for custom music is simply impossible.

So what are you to do? Unless you want to make the music yourself, you’re likely going to turn to game music packs.

Game music packs are exactly what you’d expect: an assortment of compositions usually grouped by a specific style, genre or sound palette.

These are absolutely golden opportunities for composers. Why? Because you not only have an opportunity to make some passive income, but it’s a perfect introduction to a budding developer.

If the hypothetical indie game dev loves your music, who do you think they’re going to contact for a custom score when they do have a budget?

It’s a win-win: devs get music at an affordable price, your music gets placed in a game, you build inroads with the developers and you get some passive income on the side.

How to make a game music pack

Steven Melin has an incredible step-by-step guide on making game music packs. He’s living proof that the process works and that it’s very possible to make a significant portion of your income with game music packs.

Check out his tutorial on the topic below:

In addition to Steven’s advice, here are some more things I’d recommend doing when making your game music packs.

Study the best with a competitive analysis

I come from the digital marketing world. One of the first things we do when we’re entering a new market or trying to expand our market reach is a competitive analysis.

This means analyzing the top performers in a particular niche or vertical and figuring out how we can create even more value for this particular market.

If you’re at a loss for what kind of game music is in high demand, this is a great place to start. The idea is to find the overlap between what market demand and the kind of music you’re skilled in.

Here’s how I might go about doing a competitive analysis.

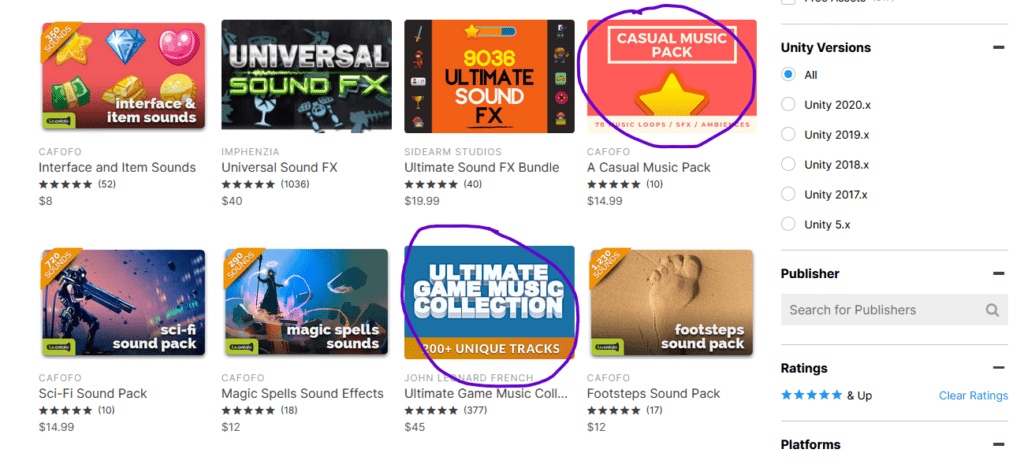

Step 1: Look at the top performers in the most popular marketplaces

The first step is to find the marketplaces that are most popular with developers. As of this writing, they are:

- Unity Asset Store

- Itch.io

- Game Dev Marketplace

Another good one is the Unreal Marketplace.

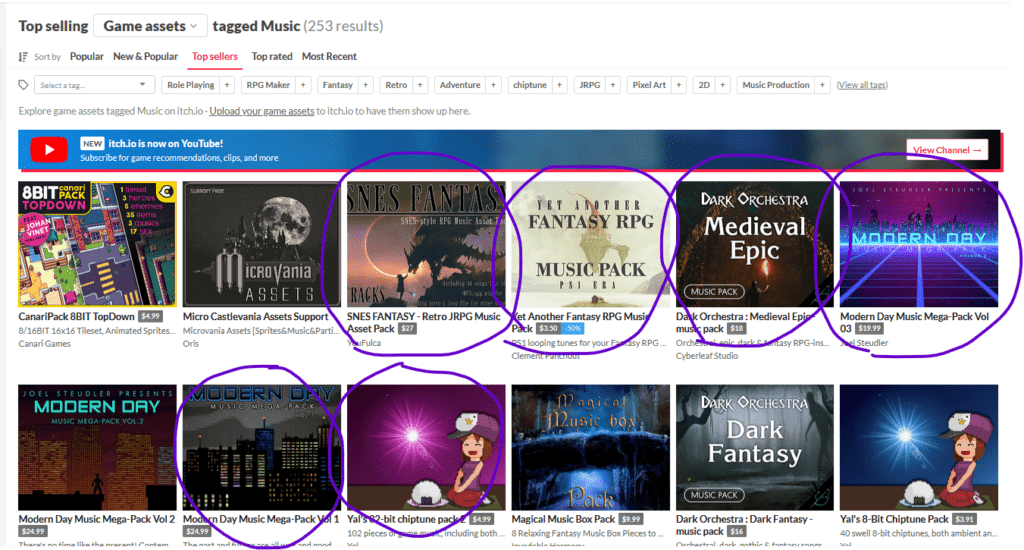

Pick a marketplace, navigate to the game music assets section and sort by “most popular” or “highest rated.”

On the Unity Asset store, I sorted by 5 stars and up in the filter. I immediately noticed these two packs on the front page: “A Casual Music Pack” and “Ultimate Game Music Collection.”

I right-clicked and hit “Open in New Tab” for analysis later.

Then, I did the same thing on itch.io. Interestingly enough, the packs on itch.io seemed to be more focused toward SNES-sounding JRPGS and orchestral music. Good to know! I opened them in a new tab.

Just rinse and repeat this process until you have about 5-10 music packs that you believe are in your wheelhouse.

Step 2: Analyze for weaknesses

The next step is study each aspect of these music packs and look carefully for areas of weakness. This crucial step is what will help you rank higher on these marketplaces and land more sales.

Here are a few things to look out for:

- Is the artwork gaudy, cheesy, or amateurish?

- How many tracks are there? Can I produce more at the same (or higher) quality?

- Is the description helpful, robust, and clearly written?

- What are people in the comments saying? Is there something they like/don’t like that I could capitalize on?

The answers to these questions will determine your actions in the next steps.

Step 3: 10x the value

We have this saying in digital marketing (specifically SEO), that if you want to rank high on Google, you need to provide “10x” the value of your competitors.

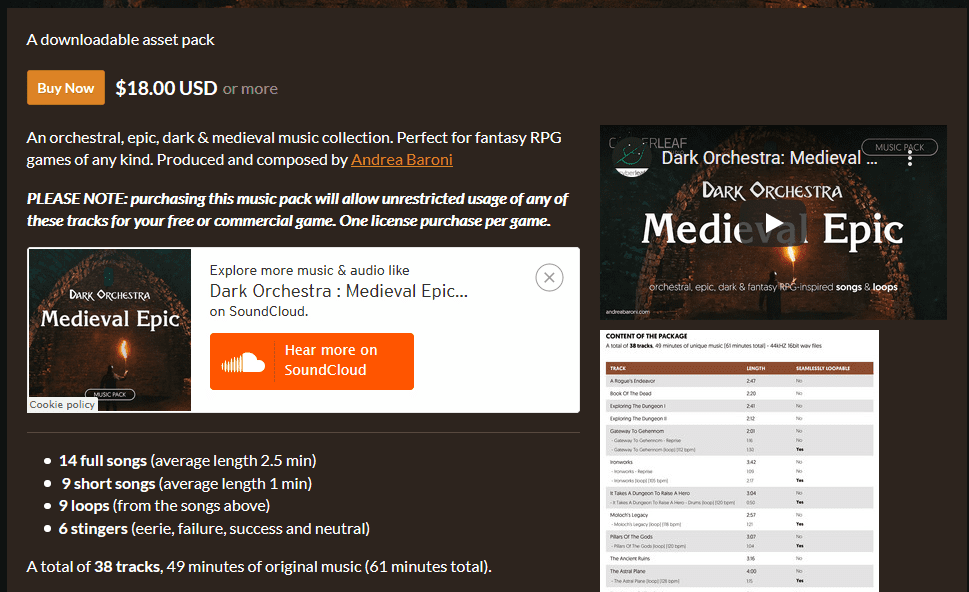

I reckon the same is true in game music pack composition. For example, take a look at one of the top sellers on itch.io: Dark Orchestra Medieval Epic

The artwork is decent, but not amazing. It’s clear that it was probably put together by someone who doesn’t have a background in graphic design.

Regardless, the sounds of the tunes are polished, interesting, full, and rich. It offers exactly what the title advertises.

As the description says, there are 14 full songs, 9 short songs, 9 loops, and 6 stingers.

So now you have your roadmap:

What if you put together a Dark Orchestral Epic Music Pack with twice as many songs?

What if you hired an artist on Upwork or Fiverr (this can be done excellently for under $50) to create a breathtaking custom album art for this?

Is this a lot of work? Absolutely.

Is this a surefire way to rank highly in these marketplaces and gain all the benefits I covered above? Absolutely.

Music packs are an incredible way to hone your craft, make inroads with creators, and make some passive income. But they require work and a lot of patience.

If you’re willing to put in that work while you build your portfolio and your reputation as a composer, you will reap the rewards for many years to come.

Pillar #4: Build your active income portfolio

Once you’ve honed your craft on music packs and started building some passive income, it’s time to move on to active income.

What is active income?

If passive income (or automated income) is income that requires little to no maintenance from the recipient once it’s set up, active income is the opposite: good ‘ol time for dollars.

I know in the previous section I kind of poo poo’d on active income, but it’s got a significant place in your income portfolio.

In fact, active income gigs — usually custom composition gigs — are notoriously some of the most lucrative things you can spend your time on.

Plus, this is the dream right? Isn’t this why we got into this business, to write custom music for games?

Let’s talk through some actionable strategies you can implement to grow your active income revenue.

Building your lead acquisition strategy

Allow me to put my marketing hat on. Yes, I’m a firm believer in building relationships. Yes, I care way more about my friendships in this industry than anything else.

At the same time, you must consider how you’re going to acquire leads as a game composer. You need a robust lead acquisition strategy that’s repeatable and scalable.

There are two types of ways to acquire leads. Outbound marketing, also known as “push” marketing, is the discipline of actually going out and banging on metaphorical doors to find work.

It’s the “hit the bricks, pal” mindset from Glengarry Glen Ross. The dreaded cold call (though it doesn’t need to be dreaded).

Inbound marketing, also known as “pull” marketing, is when you create things that draw in your target audience.

These things often include a marketing funnel, an email list, and a “lead magnet” that you use to capture emails and market to them later.

Included in inbound marketing is brand-building; or building an audience online where people know and trust you, kind of like how Steven has on YouTube.

At the beginning of your career, your marketing breakdown will probably look a lot like this:

And that’s okay. You can’t expect to have the same name recognition as Tom Salta or Grant Kirkhope overnight.

Nobody is desperately beating down your door to score their game. That would be kinda weird if they were, right?

But, as your career grows, as you start to develop repeat business and a solid reputation in the industry, your marketing breakdown will probably look a lot like this:

You’ll suddenly realize you don’t have to do as much prospecting anymore, that people are actually coming to you now.

That you’re the commodity that people want, as opposed to approaching devs with hat in hand begging them for a chance.

With that preamble out of the way, let’s take a look at some practical examples of both outbound and inbound marketing in the game composition space.

Outbound marketing

Networking

Obviously, outbound marketing is centered around reaching out to people and making connections with them. The hope is that these connections lead to some sort of mutually beneficial business outcome or working relationship.

Or, if not, just a supportive friendship and another ear to bounce ideas off of.

There are really only two types of networking:

This is by far the most preferable form of networking, even for an introvert like me. The quality of the friendships you make at meetups, conferences, or game jams are infinitely more powerful than sending a bunch of cold emails.

That’s not to say you can’t become close friends with people through the internet — it happens all the time, even in my life as a busy dad with two kids. My point is that making inroads in person is so much easier than online.

If you’re an introvert like me, sometimes it’s helpful to bring a friend along. I find that my confidence level to approach a stranger is much higher when I have someone with me.

Also, you’ll probably want to plan out a few things to say to folks should you have the opportunity to meet them.

Here are some helpful ice-breakers you’ll want to have in your back pocket:

- “Hey there! So what brings you here today?” An all-around great open-ended question that gets the developer talking about him or herself. They will likely reciprocate the question, which may be a good open door to talk about your work as a composer

- “What challenges have you encountered in the development of your project?” This is relevant to devs who are showcasing their game (often at meetups or conferences) and, once again, can get them talking.

- “Do you mind if I play it?” It’s amazing how many folks are reticent or nervous to play a game that’s being demoed. There’s no better way to strike up an organic conversation than to just go up and start playing whatever game is being displayed. This is, after all, their pride and joy.

Another tip is to have a flash drive with one or two of your music packs on it (you did make music packs like I said in the last section, right?) and hand them out to developers like business cards.

No charge, just, “Hey, it was great speaking with you! I’d be honored if you considered using my music in your game. No charge, here’s a USB drive with some free tunes on it. Let’s keep in touch!”

That will absolutely blow a developer’s socks off. And, going even further, you can record a video of yourself on the thumb drive thanking them for considering your music and giving them next steps if they want to hire you for a custom score.

The great thing about game audio and composition is that there really isn’t a central “hub” city like New York are to film composition.

Everyone is connected through the internet, and it makes for a really supportive, inclusive and engaging global community.

Here are some great places to find developers and fellow composers to network with:

- Facebook groups – There are lots of very active indie developer and composer Facebook groups. Just do a search for some keywords like “game developer” and “game audio” and filter by groups. You’ll find ‘em.

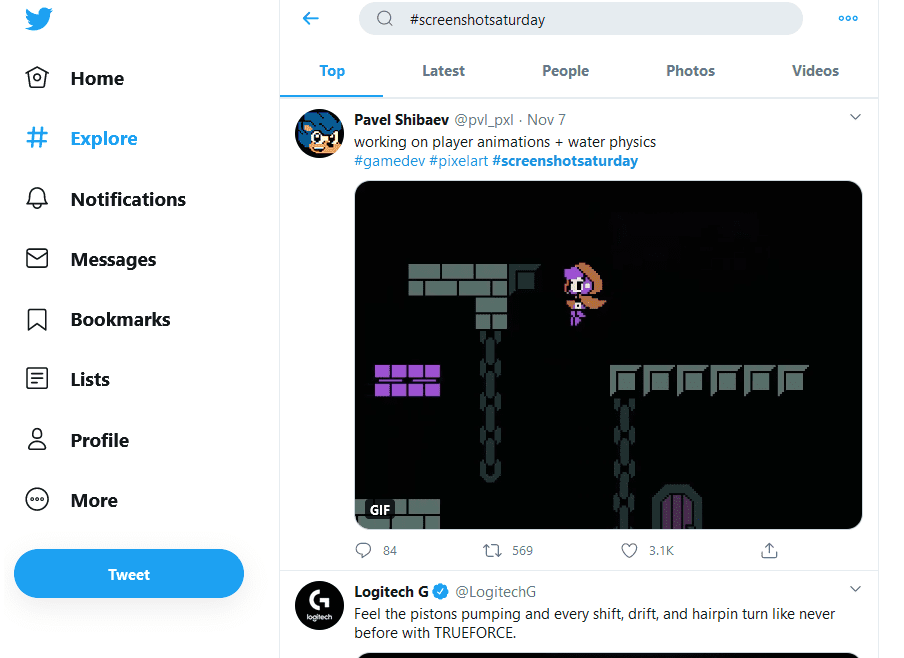

- Twitter hashtags – I would recommend closely following Twitter hashtags like #indiegamedeveloper and #screenshotsaturday. “Screenshot Saturday” is a widespread weekly tradition where developers from all over the world post work-in-progress screenshots of their games. It’s an excellent way to start a conversation with a developer that you may end up working with.

- Forums – just do a Google search for “video game music + forums,” “indie game developers + forums,” or any other permutation of these keywords. Google will limit the results exclusively to forums so you can see where the industry hangs out and what they talk about.

How to cut through the noise with free demo tracks

A great strategy to cut through the noise of fellow composers cold-emailing devs is to offer to compose a free demo track for a developer.

The process is easy:

- Identify a developer or a game that piques your interest and fits in your composition skill set (Screenshot Saturdays are great for this)

- Offer to compose a free demo track for their game in a private message

- If they respond, ask a few diagnostic questions about what they want the tune to sound like and what sound palette they’re looking for (try to get some reference tracks if you can)

- Deliver an excellent piece of music in the next week or so

Steven Melin (and others) have used this process with great success.

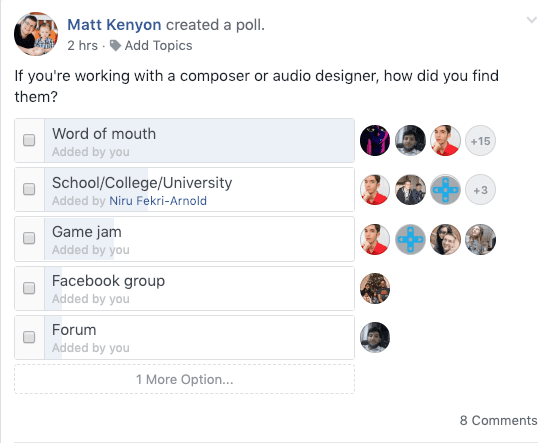

How do developers find and partner with composers? (Game Audio Survey)

So a few years ago, I polled a bunch of game developers on how they find composers. I found the answers extremely insightful.

You can find the full synopsis of my research in this post.

Now, it’s no surprise that word-of-mouth connects the most developers and composers. This is marketing 101. If your best friend tells you to hire a particular plumber, you’ll probably hire that plumber, regardless of what anyone says online.

But the conclusions I draw from these responses are twofold:

- Word-of-mouth gigs come most often from other composers who either refer you because they’re wanting to help you out, or they refer you because they’re too busy to take the gig. Therefore, building strong relationships with other composers is a must.

- If you don’t currently attend a university, game jams are the third best way to meet people (several devs say they met and partnered with composers on several projects after meeting at a game jam)

Inbound marketing

Alright, now that we’ve unpacked some practical outbound marketing strategies, let’s look at inbound marketing.

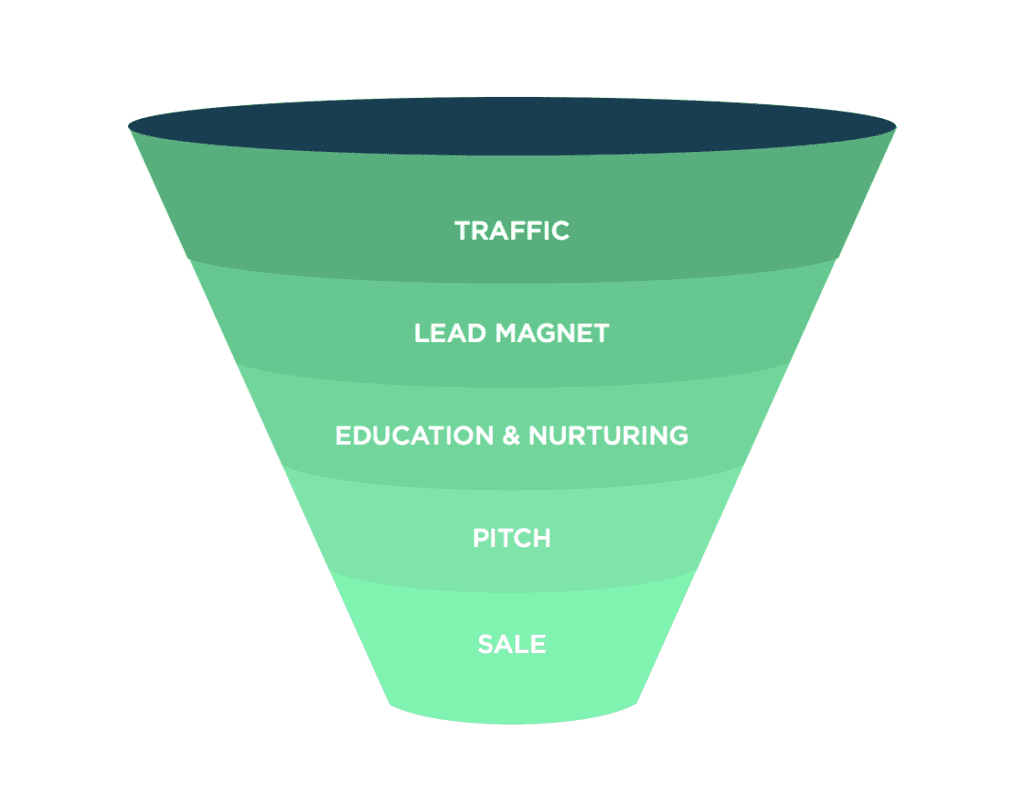

Implementing a marketing funnel

In the digital marketing world, we live and die by funnels. Marketing funnels exist because people aren’t always ready to purchase your goods or services as soon as they meet you.

For that reason, we have to “nurture them” down the funnel.

The top of the funnel is general, free content with a wide appeal like YouTube videos or blog posts. You use these free tools to then drive people to your website, where they give their email address to you in exchange for a free “lead magnet.”

Lead magnets can be helpful PDFs, checklists, or even the very same game audio packs mentioned above.

Then, once you’ve gotten their email address, you continue to send them valuable content and resources through regular email communications. Ideally, they will soon be “warmed up” and ready to purchase from you.

Real-life composers who are killing it at inbound marketing

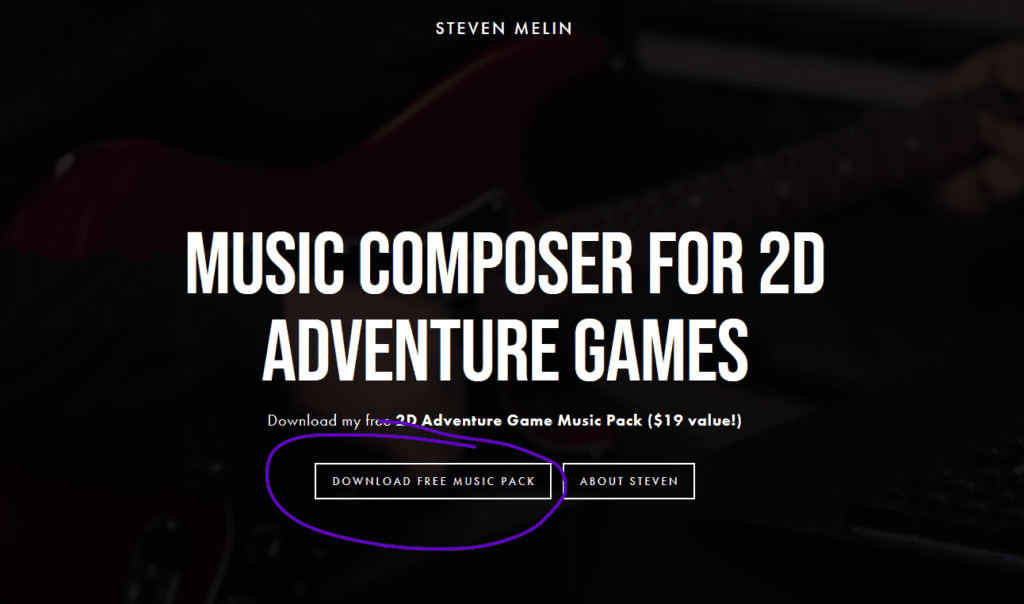

Steven Melin

This is best illustrated with an example. I know I’ve mentioned him a few times in this post, but that’s because he’s doing a lot of great stuff in this space.

Steven Melin uses ConvertKit, a powerful, freemium email platform, to maintain his email list and his funnel.

This is how his funnel works:

He draws people in with free resources like YouTube videos, blog posts, and music packs.

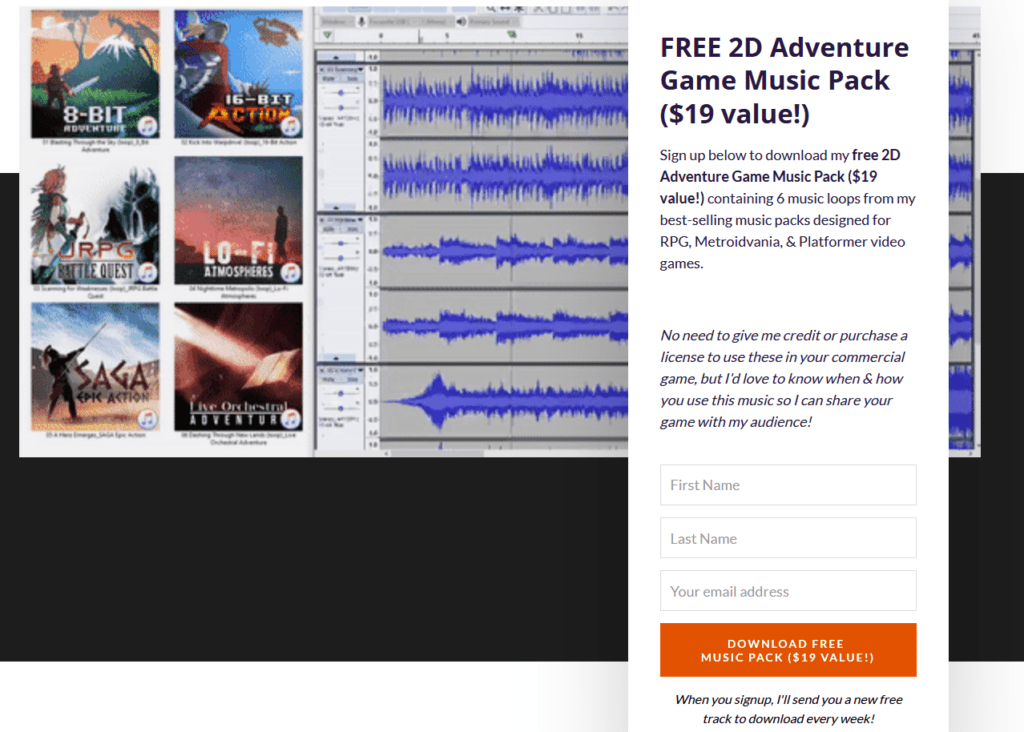

Once you arrive on his site, you’re greeted with a splash screen with two options “Download free music pack” (this is the lead magnet) or “About Steven” (which takes you to the rest of his site).

Once you click the lead magnet link, you’re taken to this page where you’re prompted to enter in your name and email in exchange for the music pack. It’s a seamless experience, and now Steven is free to add value to you through email until you’re ready to hire him for custom music.

Brian Skeel

Most folks online (including me) will tell you “you gotta have a demo reel, you gotta have a portfolio.”

But how do you keep your demo reel from looking like everyone else’s? My buddy Brian Skeel is a great example of someone who’s using an excellent demo to build his authority as a competent composer, sound designer, and even sound programmer.

On his site, rather than having a smattering of clips set to his music, he has a full-fledged tutorial where he explains how he created custom music, sound effects, and voiceover audio for a demo project.

He walks step-by-step through the composition and sound design process, as well as showing screencaps of how he used middleware and game engines to implement the music into a fully-functioning game.

This is incredible, and going the extra mile like this is a surefire way to impress prospective developers and establish your expertise.

Check out his full demo reel landing page here.

Alec Weesner

Alec Weesner is a composer (and good friend) who demonstrates his composition skills by publishing YouTube videos recreating and analyzing popular video game tunes.

This not only helps him hone his craft, but also establish himself as an authority and expert in the composition space.

Winifred Phillips

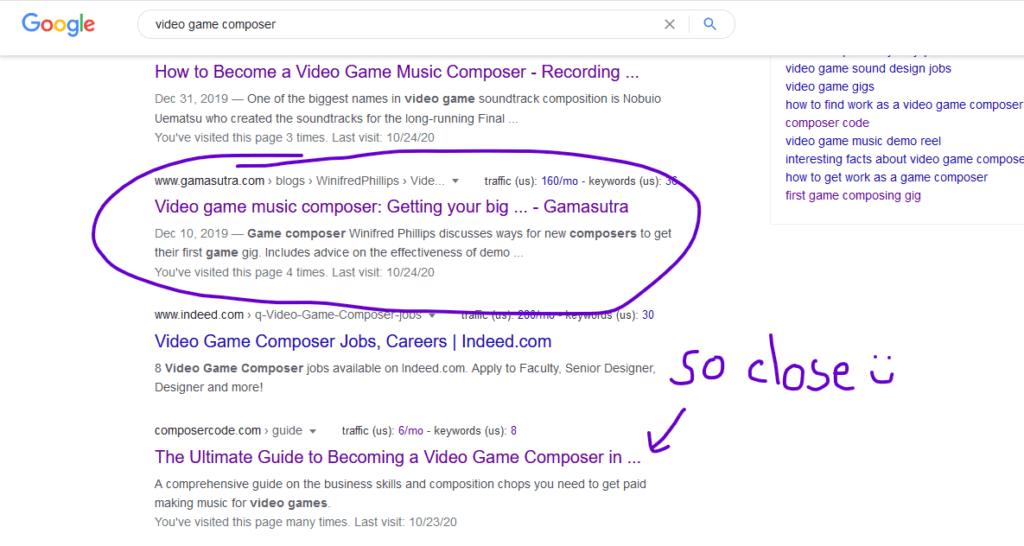

Winifred Phillips (composer of Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation and LittleBigPlanet) establishes her well-earned credibility in the game composition space by writing large, authoritative articles on how to become a game composer.

These pieces are picked up by huge publications like Gamasutra, which means they rank very highly in Google.

Take a look at the search results for “video game composer.”

This means that Winifred has the name recognition not only for her work on AAA games like God of War and Assassin’s Creed, but also the clout of being one the top-ranking experts on this particular subject.

Being that this particular article gets around 160 hits a month, I have no doubt people reading this are then funneled to Winifred’s site and her own music.

Therefore, guest-posting for big publications like Gamasutra is a fantastic way to build credibility and get your name out there.

Pillar #5: Consistently deliver excellent work

The fifth pillar of succeeding as a game composer is to consistently deliver excellent work once you’re hired.

The best way to get repeat business and positive word-of-mouth recognition is to do great work. It’s that sample.

So, with that said, what are the first steps you should take when you finally land the gig?

1. Make a Game design doc (or creative brief)

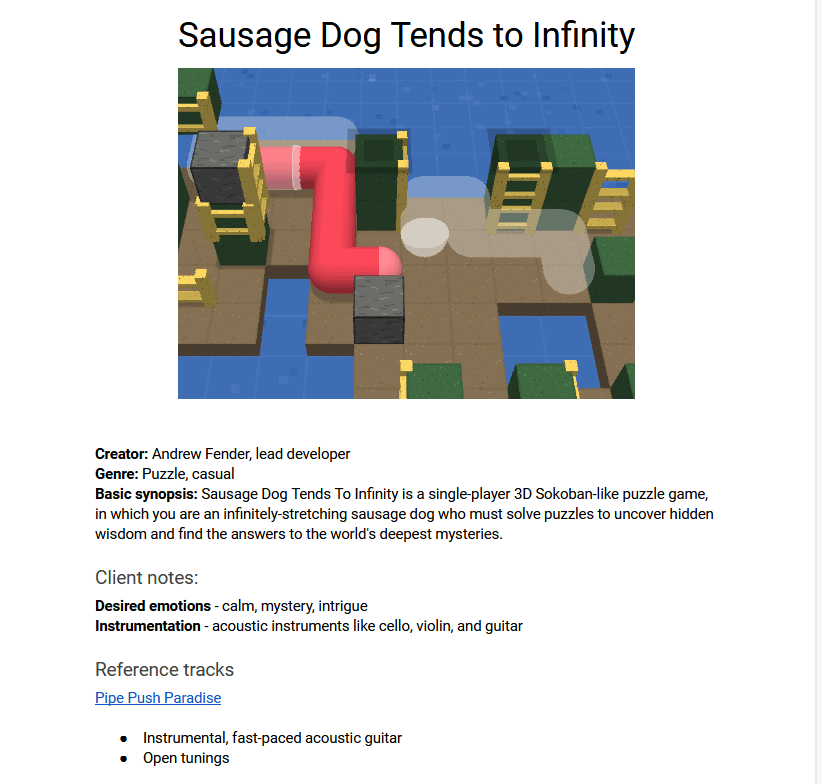

The first thing you’ll want to do once you land the gig is create a game design doc (also known as a creative brief).

This is a comprehensive document that should contain:

- An overview of project

- The goals of the music

- Any specific moods, genres, or feelings requested by the developer

- The number of assets required

- The asset deadlines

- And potentially many more things

You’ll then want to have a separate section for each asset. For example, you may have a main theme asset contained in this project.

Make a subhead in your Google Doc (or Word Doc), name the asset, and describe it in as much detail as possible.

You want to have as concrete a plan as possible before you hit up your DAW. This will help you avoid “thrashing” in your DAW, or just randomly adding tracks and bits and bobs to fill the song out without any clear intention.

2. Give the client a Onboarding questionnaire

If you’re wondering how to fill out your creative brief, I would recommend sending your client an onboarding questionnaire.

You can make one of these in Google Forms, or simply ask the following questions via email:

- How do you want players to feel during this particular song?

- Do you envision a particular genre or instrumental aesthetic within your game?

- What are 2-3 of your favorite game soundtracks that you’d like to draw from for your game?

- Can you link me to 2-3 reference tracks of tunes that you really like and specific things you like about them?

- Do you want music to loop continuously until a level is completed or change based on certain game states?

- Do you need implementation via a third-party program?

- Are there any specific instruments, genres, or particular musical elements you really don’t want?

The answers to these questions will provide a ton of insight on how to move forward.

3. Deliver A Statement of Work

Next up, you’ll want to draft up a statement of work. Before you compose a single note, you’ll want to write up everything you understand about the client’s project and their musical vision.

This will prevent any headaches or miscommunications down the line. In addition to this, your statement of work should include:

- Your exact deliverables

- What format they’re delivered in (.wav, mp3, FMOD or middleware files)

- If you’ll be doing any sort of implementation

The polish of your SOW matters way less than the content. That said, it’s good to craft an aesthetically-pleasing slide deck in a tool like Keynote or Google Slides and export it as a pdf for that added touch of professionalism.

4. Draft A Contract

Once your client agrees on everything outlined in the SOW, it’s time to draft up a contract. A contract is a legally-binding version of the SOW.

Do I think you will ever be sued (or sue) someone for shafting you in a composition deal? No, I really don’t. It almost never happens. You know why it almost never happens? Because a contract exists.

A contract is like a security camera. Realistically, if there is any actual wrongdoing, it won’t do you much good. Just like if someone with a mask on breaks into your house, a security camera doesn’t do you much good.

Your legal fees and court costs will likely be so much more than any money you miss out on, especially early in your career.

What a contract does (much like a security camera) is signal to your client that you’re serious. Most often, it acts as a deterrent of any misconduct.

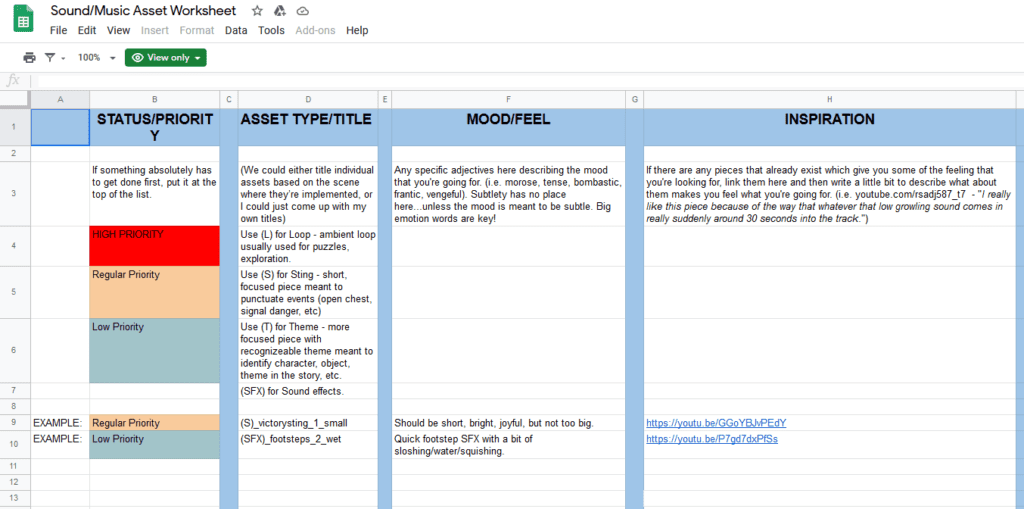

Asset sheet

Once you’re off to the races, I highly recommend creating a musical asset sheet to stay organized. You can easily do this in Google Sheets or Excel, and the 20 minutes it takes to set up will save you a ton of headaches.

This is especially true if you’re doing any sort of sound design or you have over five assets. You think you can keep track of them all in your head (trust me, I’m a perpetual optimist).

I’m telling you right now, you can’t. Don’t depend on your memory, get an asset sheet going.

It doesn’t need to be complicated.

Wrapping up

Phew! That was… a lot of words! I’m glad you made it to the end, and I hope it means you found this content valuable.

I hope that, wherever you are in your game composition journey, this post will be a guide and reference to you for years to come.

I love hearing about my readers and their success. If you like this content, please shoot me an email at kenyon.matt@gmail.com

Happy composing!

This article is pure gold. Thanks Matt for outlining all this valuable info in such a clear and concise way. Invaluable stuff here.

I’m going to read this in deep and check all your material for sure, thanks so much for this!