It’s never been easier for us to create incredible video game music for free. In this post, I’m going to teach you tangible strategies for making video game music at a low (or no) cost, even if you’re a complete beginner.

We’ll review the essentials of:

- Melody

- Harmony

- Arrangement

- Music Theory

- Music Technology

Everything I’m going to teach you has either been essential in my own career, or I’ve picked up from the two dozen composers I’ve interviewed on my podcast.

Watch the video version of this post (with a real-life composition!) here:

Getting set up

The first thing you need to make video game music is a digital audio workstation (DAW). I won’t spend a lot of time unpacking each DAW on the market — you’re probably already somewhat familiar with them.

There’s no one “best” DAW. At the end of the day, it all comes down to preference and your desired workflow.

If you’re between DAWs or this is new to you, find two or three that look interesting to you and download their free trials.

The key is not to dwell too long on choosing a DAW. In my experience, this is just a fancy form of procrastination. Just pick one and move on. For what it’s worth, I use Reaper.

I also really like Cubase, Logic Pro X, and Ableton Live. Reaper is free for 60 days, so if you want to stay completely at no cost, that’s what I’d recommend.

Optional gear

This violates the “free” rule, but I recommend investing in the following gear when you can afford it. That said, it’s not essential for making video game music:

- MIDI keyboard

- Audio interface

- Decent pair of headphones or studio monitors

Tips for Making Video Game Music

Tip #1: Study the kind of music you want to write

You probably have a general idea of the kind of video game music you want to write. We all have games that have shaped our tastes, typically in the formative years of our childhood.

You may have a penchant for peaceful RPG music. Or perhaps you’re partial to chiptune music from the early 90s. Maybe it’s Skyrim’s sweeping orchestral score that tickles your fancy.

Just like an author studies her favorite novels or a painter studies his favorite artists, you must study your influences.

It’s not enough to just listen passively and then try to regurgitate what you hear.

I highly recommend importing reference tracks from some of your favorite game soundtracks into your DAW and studying things like:

- Tempo

- Arrangement

- Instrumentation

- Melodic contour

- Commonalities between all your favorite tracks

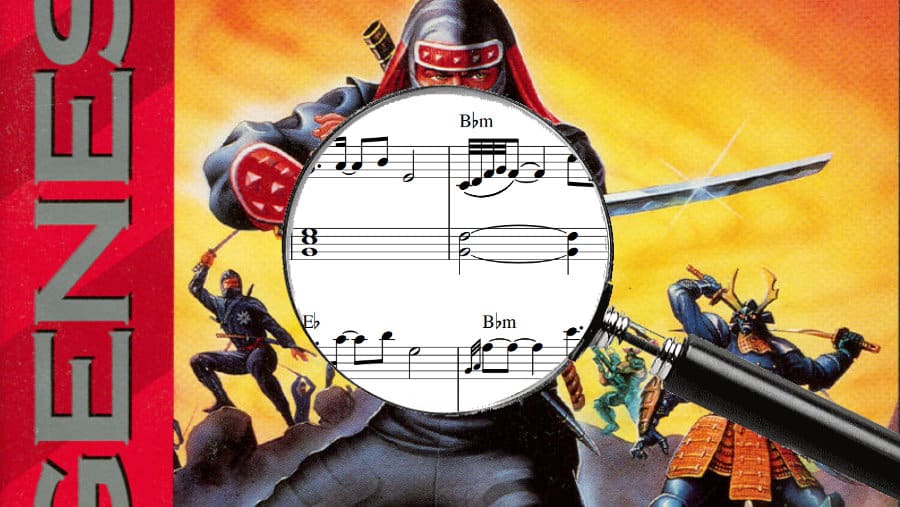

Of course, if you’ve been following my content for any length of time, you know that I’m a huge fan of transcription. It is hands-down the best way to improve as a video game music composer.

Your skills will improve exponentially if you make a regular habit of transcribing. If you’re new to transcription, check out my blog post on the topic here.

Tip #2: Make a creative brief (with or without a client)

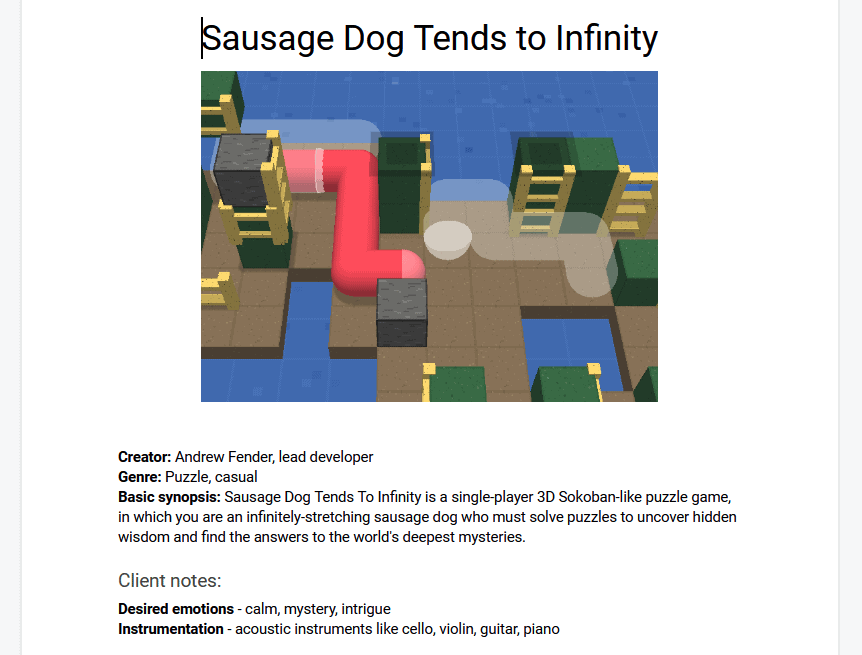

If you’re interested in eventually working with clients, you’ll want to get used to writing a creative brief.

A creative brief is like a blueprint. It’s a 2-3 page document that guides you throughout your composition process.

Even if you don’t have a client, it’s a best practice to have a guiding document when undergoing a creative project of any kind.

This doesn’t need to be complicated or fancy. Just open up a Google Doc or a Word Document and list out:

- Your goals for the composition (if any)

- How you want the listener to feel

- How your piece contributes to the scene or mood of the game (if scoring for a game)

- What reference tracks you’ll be drawing from (and what you like about them)

- The ideal length of the piece

- The desired ensemble (instrumentation)

- The form (AABA, ABABC, etc.)

It’s helpful to be as specific as possible in these planning stages. That way, when you open your DAW, you’re free to be in full-on creative execution mode.

I walked through this exercise live in the video version of this post. See how I analyzed the music of Ice Cap Zone from Sonic 3 in the above-linked video.

It may seem silly or unnecessary to create a creative brief for pet projects or even for smaller clients.

But I can tell you from experience, that every time I’ve “gone in blind” without any sort of plan, I end up feeling very disorganized and unfocused.

Tip #3: Set up your sound palette first

One of the best ways to kill your creative flow is to switch contexts.

For example, going back and forth between actually composing and digging through your sample library for the perfect instrument. This is an inefficient use of your willpower and will result in creative fatigue.

A professional chef once told me that one of the keys to cooking is preparing your ingredients in advance. The same applies to your sound palette.

I know it’s tempting to start composing as soon as you open your software, but take 20 to 30 minutes and pick out your instrumentation first. It’s like measuring out all of your ingredients in the exact proportions ahead of baking a cake.

This doesn’t mean you can’t add to your instruments later! When inspiration strikes, by all means, find the sounds you’re looking for.

My point is that switching back and forth between creation and curation will exhaust your brain faster and interrupt your flow state.

Tip #4: Experiment with layering

There are two types of musical arrangement.

Horizontal arrangement deals with how the piece evolves and changes over time. Vertical arrangement deals with how you layer sounds, harmonies, and individual voices at any given point in the piece.

One of the easiest ways to make your piece sound more rich, full, and unique is to layer sounds together.

I went through an EDM phase where I got big into producing electronic music. What shocked me when I studied the genre and watched producers work was how much they layered their sounds.

It wasn’t uncommon for producers to have six bass tracks layered on top of one another. One would cover the sub-frequencies, another the high-end. The others would give the sound “bite” and percussive quality.

However, in the context of the song, they all sounded like one unified instrument.

This was totally eye-opening, and I took this principle into my VGM composition. I commend it to you as well.

Tip #5: Start with a small idea

One of the scariest things in any creative field is a blank canvas. How do you know where to begin?

The key is to reframe your mind. Don’t open your DAW or sit down at your instrument and say, “Okay. I need to compose a piece.”

Start small. Say, “I’m just gonna find a cool interval,” or “I’m just gonna play around in the pentatonic scale.”

If you’re stumped, consider these starting points:

- Start with a scale — limit yourself to finding a melody in a minor, major, pentatonic, or some other exotic scale. Some DAWs even have a “quantize to scale” option.

- Start with a rhythm — if no melodies or harmonies are coming to mind, lay down some drums (or beatbox into your phone mic, if you want). A rhythmic foundation can be incredibly inspiring. Plus, composing to a beat is a lot more fun than composing to a click track.

- Start with a chord progression — starting with an existing chord progression and then writing your own melody over it is called a contrafact. It’s a great way to grease the wheels of inspiration. If you’re short on cool progressions, you can check out my post on the 13 best progressions in VGM right here!

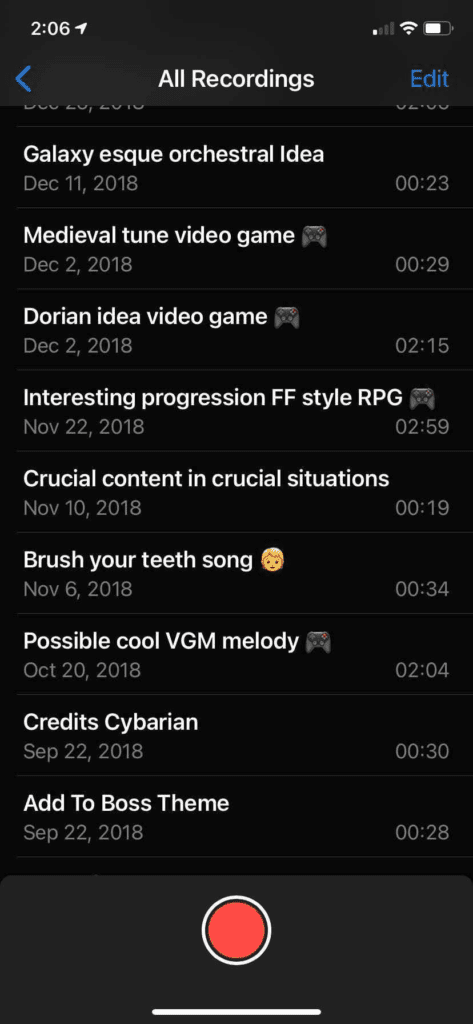

Tip #6: Keep an idea file

My best compositions have not come to me while sitting at my desk in front of my DAW, or even in front of my instrument.

Nine times out of ten, the initial ideas hit me while I’m doing menial tasks like shopping, taking a shower, or doing dishes.

Whenever inspiration hits, you must have a way to not only capture but store these ideas. The capturing factor is not really an issue anymore (I think we all know about The Voice Memos app).

However, if you’re anything like me, you totally forget about all the ideas that you’ve captured.

This means when you sit down to make game music, you start from scratch. What was the point of capturing all those ideas then?

That’s why you need a place to store them. After I record an idea, I immediately share it to a designated Google Drive folder.

I can access that folder from my composition computer so that when I open up my DAW I’m never at a loss for an idea.

And maybe that idea will come to nothing, maybe I’ll completely scrap it. But the point is, any time you can not start from scratch, you’re going to be that much more productive and efficient in your composition workflow.

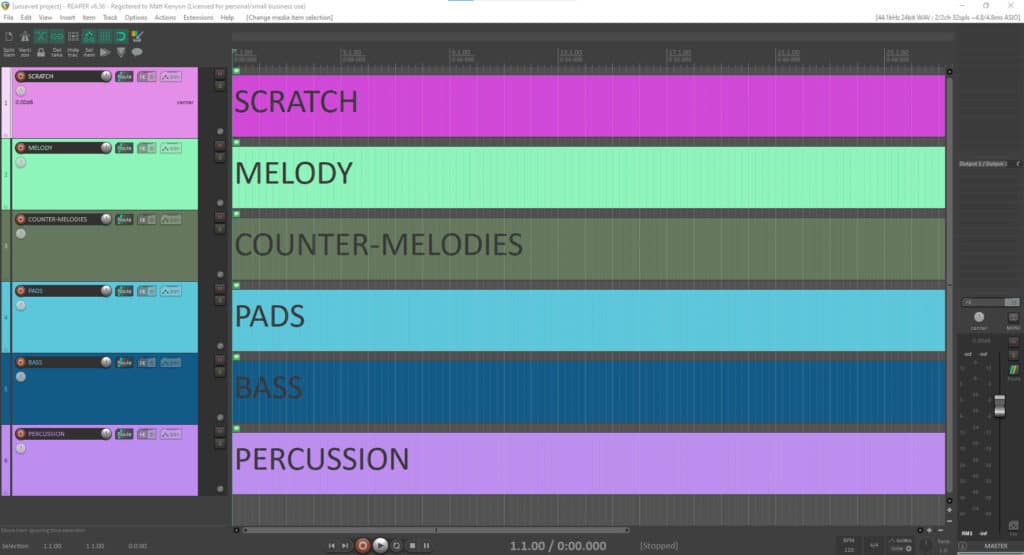

Tip #7: Build out the structure early

In an earlier tip, I recommended studying musical form.

Composers use forms to keep listeners engaged. It keeps things familiar, yet interesting.

Consider the tried and true pop song form:

- Intro – 4 bars

- Verse – 8 bars

- Chorus – 8 bars

- Verse – 8 bars

- Chorus – 8 bars

- Bridge – 8 bars

- Chorus – 8 bars

- Outro – 4 bars

Use markers and regions to set up this structure in your DAW before diving into a composition. Or, you can simply write this out in your creative brief or on a piece of scrap paper.

Things get much more complex in dynamic music systems, but at least planning out some semblance of form before you start composing can really help you have a clear endpoint to your piece (and each of your sections).

Tip #8: Keep melodies singable (or don’t!)

When the average person hums a song in the shower, they’re probably not humming the bassline or the beat.

Nine times out of ten they’re humming the melody. And when someone can’t sing the melody, it’s less likely to get lodged in their brain and leave a lasting impression.

However, this tip should be applied on a case-by-case basis.

The original Mario Bros Overworld theme is the most iconic video game composition of all time. It’s full of massive leaps, syncopated rhythms, and over an octave range.

I’m a trained singer and it’s tough for me to sing that tune. That’s why these are tips and not prescriptive rules.

They don’t work in every situation — they’re tools you can have in your toolbox.

Tip #9: Utilize repetition

Repetition is one of the most powerful tools in the composer’s arsenal.

Not only does it unburden composers from constantly writing new material, but the perfect amount of repetition keeps things both familiar and interesting.

This is much more of an art than a science, and I give a couple of examples in the video version of this post.

My best recommendation would be to bring reference tracks into your DAW and study how often the form repeats. Study how often it introduces new material and try to replicate those techniques in your own compositions.

Tip #10: Keep the melody on top

This next tip deals with vertical arrangement.

Listeners can most easily identify the highest and the lowest pitches in music. The “inner voices” are harder to distinguish (which makes them a lot tougher to transcribe!)

For that reason, it’s generally a good idea to make your melody the highest thing (in terms of pitch/frequency) in your composition.

This isn’t a hard-and-fast rule — great songs violate it from time to time — you may just find that it’s tougher to hear your melody when it’s buried among other instruments.

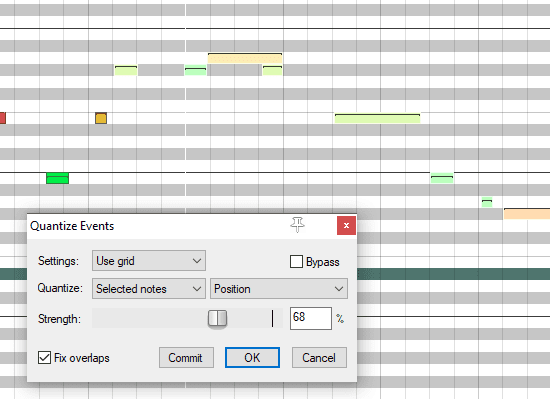

Tip #11: Quantize intelligently

Quantization — snapping notes to a grid — is a double-edged sword for composers.

On one hand, it helps composers save time by not having to repeat sections until they get a perfect take. On the other hand, a perfectly quantized piece can feel inhuman, stale, and cold.

This feeling is especially true when composing with expressive instruments like violins, pianos, guitars, woodwinds, and the human voice.

I recommend intelligent quantization. Purposeful quantization.

Most DAWs quantize on a strength spectrum. Meaning, you don’t have to lock things to a grid but you can guide them toward the grid.

Most DAWs also have a “humanize” feature which adds subtle variances in timing, velocity, and note length — much like how a human would play an instrument.

Tip #12: End loops on a dominant chord

If you’re making looping video game music, one of the toughest challenges is how to make the loop seamless. Meaning when the loop ends and goes back to the beginning, it’s not jarring or distracting to the listener.

One of the best ways to do this is to end your loops on a dominant (V) chord. This is because dominant chords want to resolve back to the main tonic chord (I).

And most of the time (but not always) the I chord is the first chord of the piece.

Tip #13: Try an arrangement checklist

You will inevitably find certain things in your composition workflow that you do over and over again. Try systemizing those things into a checklist.

That way, whenever you’re stuck, lost, or overwhelmed, you can refer back to your checklist and know exactly what you need to work on next.

This could apply to composition, arrangement, mixing, mastering, or any other repeatable discipline in your workflow.

Tip #14: Learn how to create interactive video game music

Learning music theory is important. However, you don’t need to know all music theory before composing.

In fact, that mindset is lethal to your creativity.

Far more important than learning music theory is actually just doing The Composition Thing.

Music theory will come with experience — you learn a lot as you go. You run into something in a piece that you don’t quite understand, you start Googling, and suddenly you now know what a metric modulation is.

Conclusion

I hope these tips help you make video game music. I hope you also know composing for video games doesn’t require you to spend a fortune. 🙂

If you want some specific recommendations on tools, software, VSTs, and plugins, you can check out my recommendations here.

And if you want to take your skills to the next level, I made a comprehensive course on how to compose video game music for beginners (you can take quite a few lessons for free).

Thanks for reading!

FAQs about Composing Video Game Music

There isn’t any one particular way to get into composing music for video games. Of all the guests I’ve spoken to on my podcast, no one has gotten into game audio the same way.

Taylor Ambrosio Wood started by reaching out to developers on Facebook. Jason Graves started by providing adjacently related audio tasks for clients before he got his big break. Steven Melin was offered a film score opportunity in college, which he leveraged into more gear and more opportunities.

The one common thread among all these is building and maintaining good relationships. In an industry as small as game audio, your network is everything.

This is a great question, and unfortunately, there’s no easy answer. It depends on so many variables: the size of the game, the budget of the game, your experience, the country you live in, etc.

In general, I would say that starting composers can expect to make $3,000 – $5,000 per game. More experienced composers can expect to make $5,000 – $10,000 per game. And established composers can expect to make $10,000+ per game.

Of course, these are just rough estimates. For a more accurate idea, check out my post on how much video game composers make.

This is another great question, and the answer is: it depends.

Some composers do get royalties for their work on video games. However, it’s not as common as you might think. In most cases, the composer will sign an “all rights” contract, which means they give up all ownership of the music in exchange for a one-time fee.

There are some exceptions to this rule, though. For example, Jason Graves has a royalty agreement with Crystal Dynamics for his work on the Tomb Raider franchise. And Austin Wintory was able to negotiate a royalties clause for his work on Journey.

If you’re interested in getting royalties for your work, it’s important to negotiate that upfront. It’s much harder to get royalties retroactively.

Yes, you can make a living as a video game music composer. In fact, many people do!

However, it’s important to remember that game composing is a business. And like any business, there are ups and downs. There will be times when you’re flooded with work and times when you’re struggling to find clients.

The key to making a living as a game composer is to be consistent with your marketing and always be on the lookout for new opportunities. And remember… never stop building your network.

Game composers make money by composing music for video games. In most cases, they are paid a one-time fee for their work. However, some composers do receive royalties for their work.

In addition to composing music for games, many game composers also teach classes, give lectures, and write books about game composing. Some also work as sound designers, audio directors, or music supervisors. And a few even start their own game audio companies.

There are many different ways to make money as a game composer. The key is to be creative and always be on the lookout for new opportunities.

This is the age-old question!

For freelancers, the most common way to charge for video game music is by the minute. In general, I would say that starting composers can expect to make $100 – $200 per minute of music.

More experienced composers can expect to make $200 – $400 per minute of music. And established composers can expect to make $1,000+ per minute of music.

Most video game composers work from home. This allows them to have a flexible schedule and work on multiple projects at the same time.

However, some composers do choose to work in-house at game development studios. This can be a great way to get started in the industry and learn from experienced colleagues.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question. The best way to become a film, TV, or video game composer is… well… to start composing music for films, TV shows, and video games!

I know it seems cheeky, but if you just want one single piece of advice, it’s this: don’t ever stop composing. No amount of marketing, networking, or knowledge will substitute for reps you put into producing actual music.

There are a few things that make game music unique:

Game music is interactive. Unlike film or TV music, which is passive, game music is interactive. It adapts to the player’s actions and changes in real-time.

Game music is repetitive. Because of the interactive nature of game music, it’s often repetitive. This can be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on how you look at it.

Game music is often looped. In order to avoid getting repetitive, game music is often looped. This means that the music will play over and over again until the player completes the goal or moves on to the next level.

Game music is usually shorter than other types of music. This is because game music is looped and because it has to adapt to the player’s actions.

Game music is often dynamic. Because of the interactive and repetitive nature of game music, it’s often dynamic. This means that the music will change based on the player’s actions.

There are a few things you should study to be a composer:

Music theory. This will help you understand how music works and how to create your own compositions.

Instrumentation and arrangement. This will help you understand what instruments are available and how to use them in your compositions.

Composition. This will help you understand how to put together a composition and how to structure your music.

If you want an online education without the tuition costs of a university, check out my course: Making Game Music: The Fundamentals of Composition

The music for movies is typically chosen by the music supervisor. The music supervisor is responsible for finding and licensing all of the music used in a film.

A music supervisor is responsible for finding and licensing all of the music used in a film. The music supervisor works with the director, producer, and editor to choose the right songs for each scene.

They’re often very involved in the editing process as well as the mix of the film. In some cases, the music supervisor may even compose original music for the film.

There are a few places music supervisors look for music:

Music libraries. Music supervisors often subscribe to music libraries, which are websites that allow them to search for and license pre-existing songs.

Online databases. Music supervisors also often search online databases, such as the Musicbed website, to find songs for their projects.

Composers’ websites. Music supervisors will also sometimes visit composers’ websites to find music for their projects.

If you want to make sure your music is easy for music supervisors to find, make sure to list your songs on online databases and composer websites. You can also create a website for yourself and list your songs there.

A music supervisor is responsible for finding and licensing all of the music used in a film. A composer is someone who creates original music.

There are a few ways you can build relationships with music supervisors:

Network. Attend industry events and meet-ups to meet music supervisors in person. You can also connect with music supervisors on social media platforms like Twitter and LinkedIn.

Create a website. Make sure your website is professional and easy to navigate. Include a list of your songs, as well as your contact information.

Submit your music. When you see a job posting that you think you’re qualified for, submit your music. Make sure to follow the submission guidelines and include all of the required materials.