Note from Matt: The following is a guest post from Composer Code reader and partner Tomas Ortola. Enjoy!

In 2019, Evie Segal, Tomas Ortola Stange, and Zak Kaye all met and became friends while studying composition at Berklee College of Music.

In early 2020, they took advantage of COVID lockdowns and started a Dungeons and Dragons (DnD) campaign with a few of their friends.

During the first session, Zak (the GM) threw together a quick Spotify playlist to go along with it.

As the game progressed, Tomas suggested that as composers they could write their own score for the campaign. Four years later, they’ve amassed over 15 hours of music with roughly 100 interconnected motifs.

In that time, they’ve learned a lot of lessons about what it means to compose for tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs), and the similarities and differences when composing for traditional video games.

What’s unique about writing for a TTRPG?

“Well, It’s similar to writing for video games in that ideally you’re writing a relatively small amount of material meant to be stretched over the longest period of time possible.” – (Ortola)

“Unlike games though, TTRPG’s are true improv storytelling. That prevents the existence of a ‘golden path’ so there are few if any story beats known ahead of time. You have to write your music with this in mind.” – (Kaye)

What about just using a Spotify playlist wasn’t satisfying for you?

“For now, methods for scoring TTRPG’s are simple. There are Spotify playlists, and a few pieces of software out there, but they mostly just exist to make the atmosphere more immersive, which is totally fine! But that means their capacity to really help tell the story is pretty limited. We figured that by writing our own music we could do something more interesting and unique to our game.” – (Segal)

What advice would you give to someone who’s trying to start a project like this?

“The most important thing is to keep things simple. Start with one piece of music, then the next, and allow the score to grow organically over time. You don’t want to make too many strong decisions about the music up front, cause you don’t know how long the campaign might go, or how it might develop. Sort of like TV, just with way less time and warning between big story moments.” – (Segal)

“After that, the first big hurdle is to discuss with the GM what kind of game they are running. This is separate from genre, which is aesthetic in nature, instead this has to do with style of play. For those that don’t play TTRPG’s, there are a lot of different systems out there other than D&D, and even within a single system there are many ways for the players to engage with it.” – (Kaye)

“For example, some games have lots of combat where it’s expected for player characters to die often, where other games keep characters around for a long time, and are heavy on Role-Play (RP). If the campaign doesn’t have much character focus or RP, and the GM and Players often expect characters to die and be replaced, you wouldn’t write a character-focused score.” – (Segal)

“This will also help give you an idea of what kind of tone the GM has planned for the game, and in fact it will often provide better direction than just their chosen genre, albeit that helps too.” – (Kaye)

So how does genre affect the score you’re writing?

“This part works a lot more like any media project you might be working on. Genres like Sci-fi, Horror, High Fantasy, Dark Fantasy, Mystery, go a long way in providing you musical touch points to start from. At that point you can create your sound world.”

“With both the style of play and genre decided, you can begin to think about the sound palette you’d like to use. The Players and GM act like a director or development studio in this instance, giving direction on what the score should be doing.” – (Ortola)

So how does this all apply to what the three of you did?

“So, our game is a heavy RP, character focused story, that takes place within a high fantasy world with dark fantasy elements, and a complicated political backdrop, involving a number of different nations and kingdoms. Because of that, we went with a pretty traditionally orchestral fantasy sound, albeit with some fun additions and modifications of our own.” – (Segal)

“One of the biggest things though, was the character focus our campaign has. So in my conversations as GM with each of the players, it was obvious that characters were expected to stick around for a while, with major story beats and arcs, as well as significant NPC ‘supporting casts’. The political drama elements of the setting in combination with the character focus, led us to make the essence of a lot of the score be built around leitmotifs.”

“This ended up meaning that we had to be a lot more detail oriented about what was happening musically in each track than if we had decided on a more ambient approach. After writing a few cues though, we started to discover that our soundworld didn’t provide enough structure, and that a ‘ruleset’ was needed to strengthen our process.” – (Kaye)

What’s a “ruleset”?

“We think about it like more specific details on how one is considering the whole composition process for the particular campaign, or in a lot of cases what the limitations are that you want to give yourself.”

“The soundworld helps to think about basic orchestration and melodies, but we needed some more concrete ‘rules’ to help in composition. Based on whether or not you or the GM decided to be more atmospheric in the music or story focused, you’ll need different ‘rulesets’.”

“In our case, our ‘rules’ were an extension of that leitmotif-heavy approach with orchestrational, harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic details being assigned meanings to help us tell the story. For example, each character has their own melody assigned to them.” – (Ortola)

Examples of rulesets in action

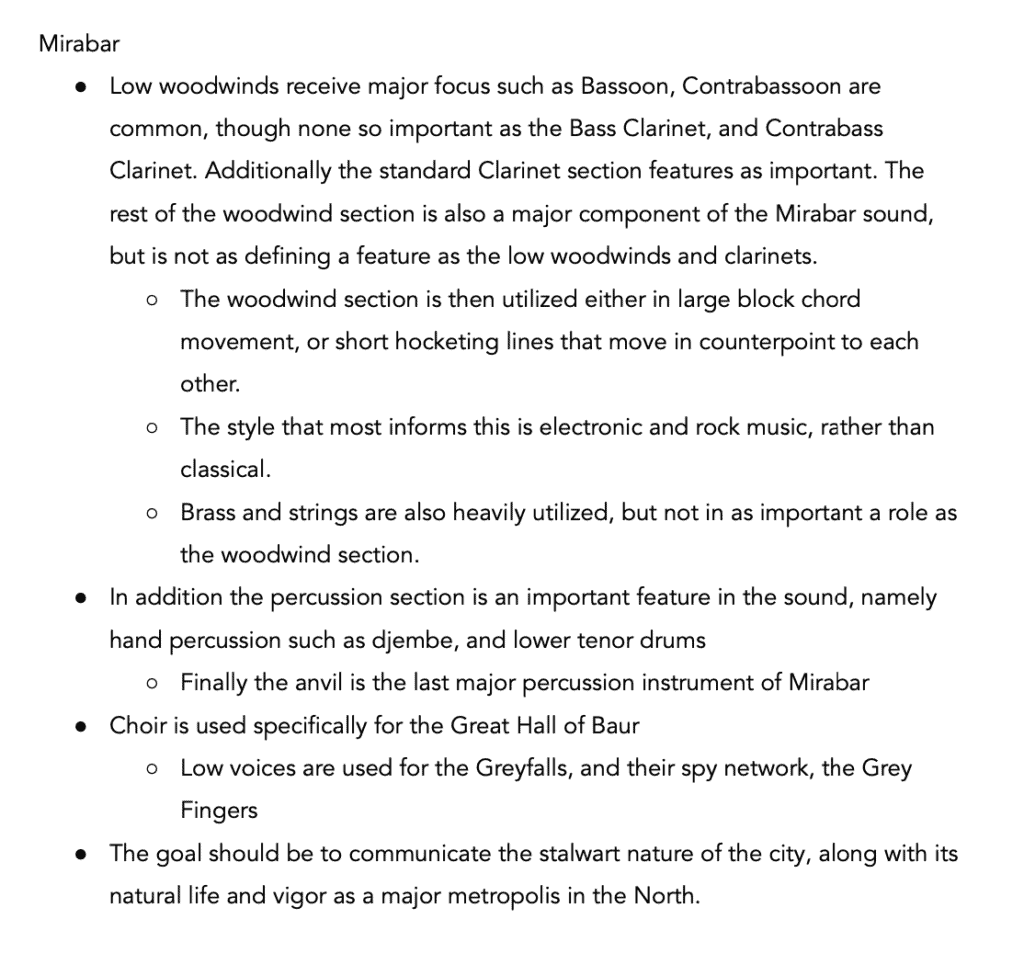

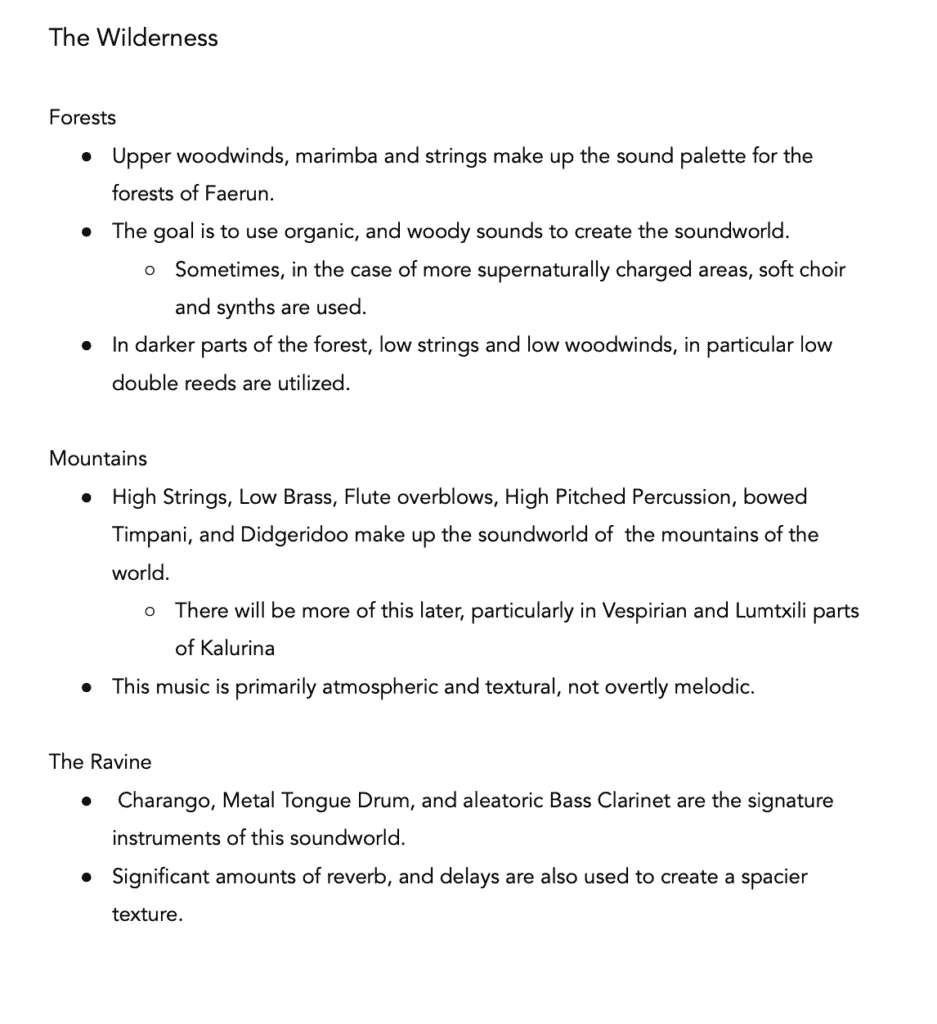

New Atisan, a location in the game, include music with a particular rhythm, pictured below:

The team also put together a sort of creative brief for each location, very similar to the creative briefs I (Matt) recommend creating for clients!

This helps so much with world-building, getting unstuck from writer’s block, and having a reference to turn to for ideas:

“The one thing is though, don’t get too specific or dogmatic with those ‘rules’. You don’t want to confine yourself too much with your decision making, so expect some of your own rules to be broken.” – (Segal)

So how regularly were you writing music for the campaign at the beginning?

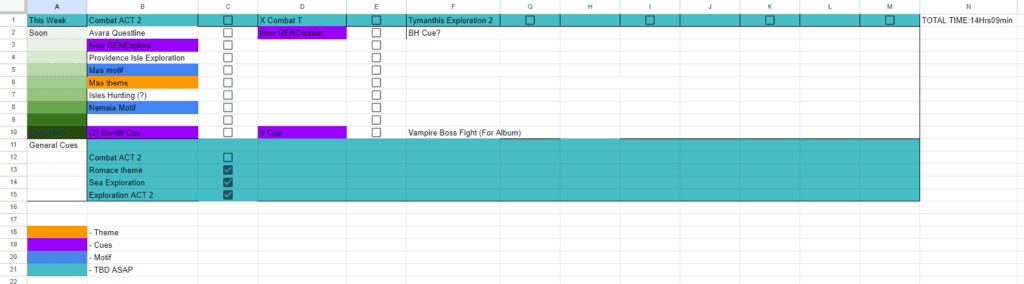

“About one track per person, every week. Later we moved to having sessions every other week, so roughly one track per person every 2 weeks.” – (Kaye)

How did you go about maintaining that output?

“It is a lot of music, and since we decided we wanted to have music that helped in the storytelling, we needed our approach to composition to do the heavy lifting. We had already landed on this motif heavy approach, and that combined with our ‘ruleset’ and orchestration ideas led us to create a lot of interweaving material that could build off itself. That does a lot of the heavy lifting for you when you’re trying to decide what musically needs to happen in a cue.

“The most important thing though was to create categories for cues to fall under; exploration, tension, stealth, combat, etc. like you might in game scoring. Those concepts combined are really what makes it possible for us to maintain that output for an extended period with such an evolving story.” – (Ortola)

So we’ve talked about how setting up a ‘ruleset’ helps to conceptualize how you’ll approach composing cues, but what are the other parts of your composition process like?

“After figuring out the starting place for the cue, and deciding on what category it falls under, our personal processes diverge pretty drastically. That said, one thing that is consistent with all of us is really making sure we take the time to explore our ideas in each cue.”

“Keep in mind that the players are gonna be listening to this music for really long periods of time, so we need to be able to hang back a bit, and leave some in reserve. Focusing on exploring and lengthening the ideas we already have rather than writing new ones if we don’t need to.” – (Ortola)

“We make sure to avoid being too descriptive or high energy with our music, even in combat tracks. The music shouldn’t be distracting the players too much from playing the game. This also helps in making sure the music is ambiguous enough that when unexpected developments happen in the story, the music will be flexible enough to adapt to those changes.” – (Segal)

“We aren’t afraid to leave space in our music. That’s something that we learned is necessary pretty early on when composing for this kind of project. You can even test your music! Listen to it while doing something else that takes your attention like cooking, cleaning, or talking. Does it set the vibe well? Does it pull your attention too much? Chances are, you can leave a lot more space than you might think.” – (Ortola)

What advice do you have on coming up with motifs/themes?

“We’d really suggest building a network of motivic material. When your melodies are played in every other cue, every week, for hours on end, it’s not hard to make them memorable. What’s important is that you write in the musical language of your overall score. For example Fledor, one of our player characters, is a soldier who has lived a life of violence and war, so his motif was based off of our combat motif.” – (Ortola)

“Another example is the melody for the kingdom of New Atisan we showed earlier. There’s a raised 4th in the motif, which is also present in the motif for the Giants. This reflects that in the lore New Atisan is built in former Giant territory. Doing this really helps keep your musical language related, no matter how big it might get. Plus it deepens the storytelling and subtextual themes in the music, creating a rich bed of musical ideas that you can then utilize when introducing new characters, themes, etc.” – (Kaye)

“It can also help to make your musical categories more identifiable, like our combat or exploration motifs. These will always pop up in cues from their respective subtype, which creates ‘earworms’ that can keep things more engaging for the players.” – (Ortola)

“All of this results in a cheat code for material and for fast composition while still maintaining narrative meaning and purpose. We had to be careful to not let this get out of hand though. Not everything needs associated material, so don’t hesitate to drop material that isn’t relevant.” – (Segal)

What are some of your most memorable successes and failures from writing for the campaign?

“So like we said earlier, don’t box yourself in with your ‘ruleset’. When we started using instrument associations, we definitely got too stringent about it, which severely limited our orchestration options. We still use instrument associations now, just a lot more relaxed than we used to.” – (Ortola)

“If you’re pulling from a real culture’s music, DO YOUR RESEARCH. It’s something that we’ve definitely done, and I think we’ve done so fairly successfully. If you want to write for a campaign at some point though, be aware of what a GM is asking for if they do ask for real cultural associations with in-game elements and don’t use another culture’s music as ‘set-dressing’.” – (Kaye)

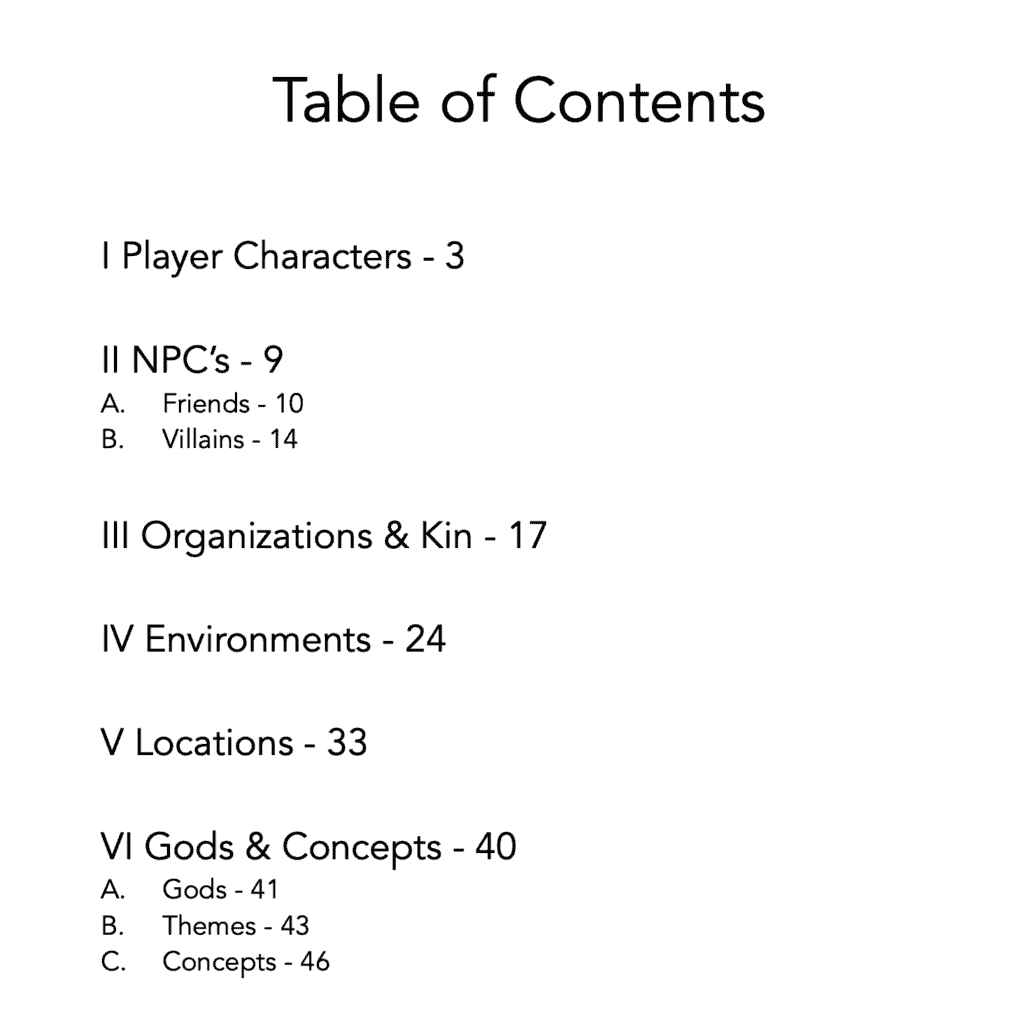

“Organization is a really big thing. Always, always stay organized about what your cue categories are, and what cues are involved in which categories. Even more than that, stay organized about your material! If the campaign is in any way longform, you will forget motifs and ideas if you don’t keep track of what belongs to what, etc.”

“By progressively getting better and better at paying attention to these details, we’ve managed to maintain a handle on a large amount of material. I think this is one of the most important things we’ve gotten right.” – (Kaye)

“In terms of our process, we’ve been very successful thinking about the PURPOSE of each cue, and orchestrating accordingly. Not just the category it belongs to, but narratively why we’re writing it. As a general suggestion try restricting instrumentation.”

“Think about every instrument you’re using and why. It can lead to more interesting results and more recognizable sonic landscapes rather than using the same ensemble in every cue, and has helped keep things fresh in our music.” – (Segal)

“By far though, our biggest success has been using all of our systems to make it so that even after 4 years, hours of music, and around 100 motifs, the music has still been able to weave into the story of our campaign so well.”

“We even had some very successful forays into using audio middleware in our sessions. It’s great that it’s all worked so well and for this much time, even though we had no idea the campaign would be where it is now.” – (Kaye)

You use middleware in your sessions?

“Oh yeah, and everything we did here was pulled straight from the realm of video game scoring. At the time, we wanted to have some interactive elements in our music, but nothing we found out there was able to do what we wanted, so we decided we had to build our own system we could put our music into.” – (Ortola)

“Middleware programs allow game composers to design interactive systems more freely by providing a visual interface for creating them. This way, things don’t need to be hard-coded into the game engine, and it’s less work for everyone involved.”

“We used Wwise for our campaign because it was easy to use its Soundcaster feature instead of creating an interface for it in a game engine.” – (Kaye)

Can you give me some examples of things you did with Wwise?

“The first thing we did in Wwise was the general combat track. The idea was that since this track was repeated more often than anything else, it could use a special “extra-lengthening” treatment. We already had it written, but by breaking it up into sections that randomly played each time, we could get a song that didn’t have a “true” repeat for hundreds of hours.” – (Ortola)

“We decided on four “Macro” sections based on how the piece was written. Then, I broke those down into sub-sections that were randomized. This way, the song always goes section A, then, B, etc., but each time they’re slightly different.”

“In section A for example, we had written each character motif, so those became the sub-sections, and every time you hear the track now it plays two character themes at random. To glue everything together, I copied a few transitionary gestures from the original track, and made those random transitionary material in between the sections. This resulted in a really organic-feeling track that could go for hours without a true repeat.” – (Ortola)

“Later, for my capstone project at Berklee, I put together an interactive system based on many of the concepts mentioned earlier. This system was designed to switch between three states of play, exploration, combat, and NPC interaction, with some additional bits of interactivity depending on the state.”

“So there are three buttons that each determine one of those states, and then for exploration there are two variations. A ‘passive’ variation which will randomly go between small subsections of calmer exploration music, specifically for the downtime of a session. Then there is an ‘active’ variation which can be used in a moment of activity where I as GM want to maybe add emphasis on something in particular. Then within the NPC interaction state I have an intensity slider which I can use to follow whether or not the players are having a positive or negative interaction with this NPC.”

“Finally there is a combat state, which is based on our previous combat system, so Wwise randomly jumps between various subsections to add randomization to the track to avoid getting too boring during combat. Additionally I added some small details by further increasing randomization though a simple random layering system.”

“This is where I have certain instruments as separate audio files that play on top of the base loop. These can then be randomized so on some loops you’ll hear different instrumental solos, or different textures via a new arrangement.” – (Kaye)

Is this something you’d like to explore further?

“The truth is, Wwise may be too niche a piece of software for most GMs to want to use. However, interfaces could easily be designed that allow for a significantly easier user experience, and that still provides more musical interactivity than what’s currently possible.”

“My personal dream would be to see this integrated directly into existing tabletop systems such as Roll20, so that GM’s don’t have to be bouncing back and forth between different software. For example, you could have it so that, when in combat, the intensity of the music is tied to how low the total health of the party is.”

“The biggest difference between this and regular game music design is that I would want the GM to be able to make decisions about what affects the music prior to a session, so that the system can accommodate different styles of play.” – (Ortola)

“We’ve always thought if we had the time that we might make a project out of this, and create an interface that anyone can use. For now we’re content with working on releasing the soundtrack on streaming so that others can use it, but excluding the interactive stuff.” – (Kaye)