“If there’s one thing I really love… it’s sad music.”

Danny Elfman, film composer

Imagine, if you will, a world without minor keys – a world without sad music.

A world in which every song was happy, upbeat, poppy, and chipper. There’s no room for feelings of heartbreak, longing, or regret – only bouncy joviality.

Ugh. Sounds awful.

The entire spectrum of the human experience can be emotionally expressed in music.

And many of the emotions we channel through our music are ones of sorrow, regret, longing, wistfulness, or anything in between.

Most, if not all of these things are made possible through minor keys. But is it really fair to pigeonhole minor keys as just being “sad”?

In this post, we’ll pull back the curtain on this critical element of music theory and talk about:

- How to build minor keys

- Why they’ve gotten a reputation for sounding sad (and why that’s not necessarily true)

- The different types of minor scales

- How to use them more effectively in your compositions

It’s about to get real sad up in here… or is it? 😉

Table of Contents

What are minor keys?

Minor keys are one of the most commonly-used musical devices in tonal music. A key is essentially a set of notes that have been organized into a particular pattern and order, known as a scale.

The most common type of minor key is the natural minor scale. This is the one that most people think of when they think “minor key.”

There are many variations of minor keys (including some of the minor modes like Dorian, Locrian, and Phrygian).

But one thing that they all share – one unifying attribute that really gets to the heart of what makes a minor key: a minor third scale degree.

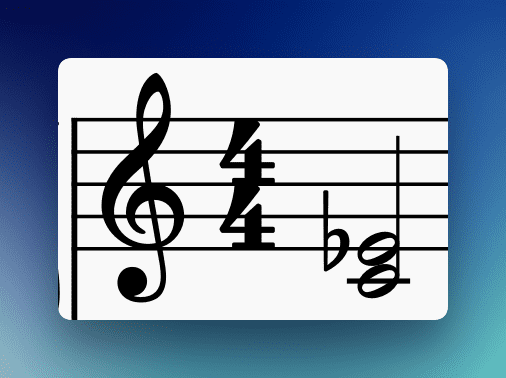

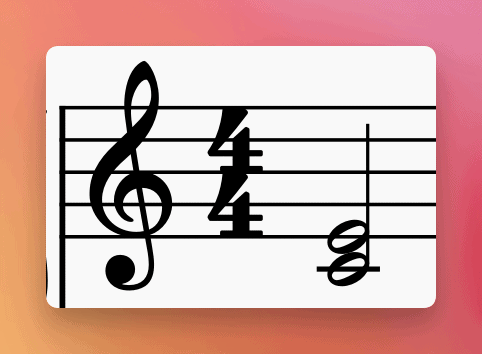

This is a minor third:

To really drive this home, listen to this in contrast with a major third:

We will learn about many different types and variations of minor keys throughout this post, but one thing they will always share is that minor third scale degree.

Remember that!

How to build a minor key

Once you understand the formula, you can build a minor key off of any note. The formula is:

Whole Step, Half Step, Whole Step, Whole Step, Half Step, Whole Step, Whole Step

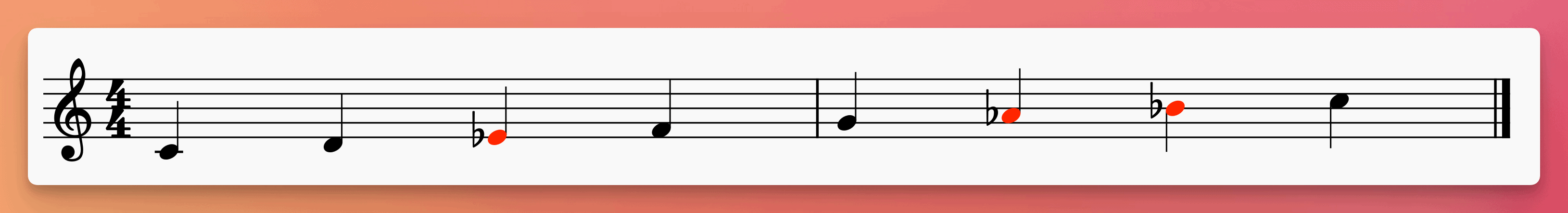

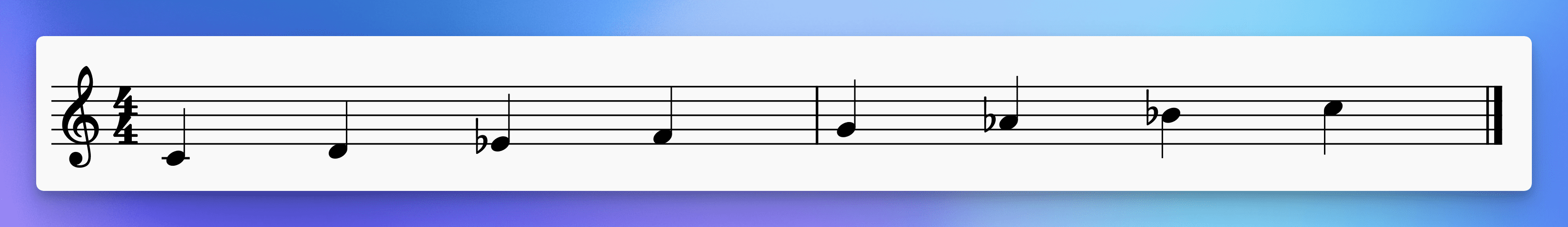

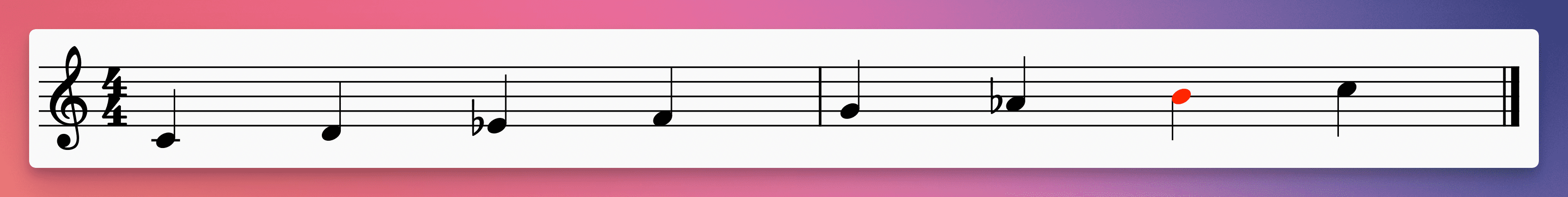

For example, if we start on note C, our scale would look like this:

C – D – E♭ – F – G – A♭ – B♭ – (C)

This is the C natural minor scale.

You can likewise build a minor scale from an existing major scale by lowering the third, sixth, and seventh degrees.

Therefore, a natural minor scale can be expressed as such:

1 – 2 – ♭3 – 4 – ♭6 – ♭7 – (1)

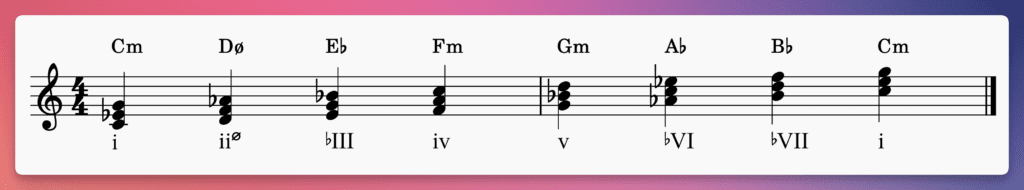

When communicating the chords of the minor scale using Roman Numeral notation, music theorists and transcriptionists will often keep the flat symbol preceding the scale degree to communicate its minor quality, like this:

i – ii – ♭III – iv – v – ♭VI – ♭VII – (i)

Why do minor keys sound sad?

This is something of a philosophical question, but many of you may be wondering exactly what makes this mathematical, formulaic combination of notes sound sad.

(The other half of you are like “that’s just the way it is, let’s get on with it.”)

For the inquisitive among you, here’s the best answer I can give you:

You have been culturally conditioned to believe minor keys sound sad.

Seriously. That’s the answer.

Some folks have tried to argue that the intonation of certain intervals is inherently darker or that minor keys have more built-in dissonance because the minor third degree is closer to the tonic.

All of the arguments I’ve heard simply don’t hold water when pushed to their logical conclusions.

The cold hard truth is that you’ve been conditioned (since you were in the womb) to regard minor keys as being associated with “darker” themes and major keys as being associated with “lighter” themes.

But that’s really just Western culture.

There are many other cultures that sing dirges and laments in major keys. Or, in Eastern European cultures or genres like Polka, their best dancing songs are all in minor keys.

And that’s a pattern Western songwriters are adopting as well.

Take a listen to Funeral by Phoebe Bridgers, and pay attention to the chords and lyrics:

I’m singin’ at a funeral tomorrow

For a kid a year older than me

And I’ve been talkin’ to his dad, it makes me so sad

When I think too much about it, I can’t breathe

Oof. That’s a gut punch (and an amazing song). And it’s entirely in a major key.

So for the sake of not being called a snob, I’m not gonna go around and point out how minor keys aren’t sad.

I still do think the prevailing cultural view of minor keys is one of sadness or darkness.

But it is important to know that this emotion is culturally conditioned, and you can write tunes that are just as gut-wrenching in major keys (or groovy bangers in minor keys).

Minor scale chords

Scales serve as the basis of chords, with triads (three-note chords) as the most common chord type.

Triads can be built off of scale degrees by adding both a third and a fifth interval from the root note.

Here’s the minor scale once more:

If we were to add a third and a fifth interval (while staying within the notes of that particular minor scale), we’d end up with these chords:

If we were to compare these chords to major scale triads, we’d notice these differences:

| Major | Minor |

| I | i |

| ii | iiø |

| iii | ♭III |

| IV | iv |

| V | ♭VI |

| vi | ♭VII |

| viiø | (i) |

But thus far, we’ve only dealt with the natural minor scale. There are actually three total minor scale variations.

Let’s take a look at them.

The three different types of minor keys

The most common minor key variation is definitely the natural minor (the one we’ve been talking about thus far).

It’s the scale that most people think of when you say “minor.”

However, there are actually three different types of minor keys. They are:

- Natural minor

- Harmonic minor

- Melodic minor

We’ve already looked at the natural minor, so let’s take a look at the two others.

The harmonic minor scale

The harmonic minor scale is one of the two variations of the minor scale that has a raised seventh degree.

It looks and sounds like this:

Notice how it is almost identical to the natural minor, but with the inclusion of the leading tone (seventh degree) back to the tonic, just like in a major scale.

The harmonic minor scale evolved back in the Classical Era as a way to facilitate the extremely important V to I cadence in minor keys.

If you know anything about classical music, you know that the V to I cadence, also known as the authentic cadence, was pretty much the standard way to end a phrase.

Well, here’s the problem: the minor scale turned that powerful V chord into a minor v chord (thanks to that flattened seventh degree), which has considerably less “oomph” when used in a V – I cadence.

The fix? Just raise that seventh degree and voila! – the minor v is now once again a V chord.

Since I’m writing this around Christmastime, it’s only appropriate to use God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen as an example of this in action.

This tune very emphatically takes advantage of the harmonic minor scale in its opening progression.

Take a listen as I play the melody and harmony first using the harmonic minor scale, then repeat it using the “normal” harmony from the natural minor scale (without the raised seventh):

Kinda falls flat, eh?

But you don’t just hear this in classical music or Advent hymns. Anytime composers want to create a stronger resolution back to the minor i tonic chord, they’ll use that harmonic minor scale (even just for a second).

The melodic minor scale

The melodic minor scale is the third and final variation of the minor scale.

It’s also the one that you’re least likely to see in modern music. In fact, I’d be hard-pressed to rattle off a well-known tune that uses the melodic minor scale without a bit of research.

It has one difference from the natural minor: it raises both the sixth and seventh degrees when ascending up the scale.

It looks like this:

Unlike with harmonic minor, where we only raised the seventh degree to create a stronger V-I cadence, melodic minor raises both the sixth and seventh degree to create a more complex sound.

To get back to the natural minor scale, you have to flatten both the sixth and seventh degrees when going down (yes, it’s sort of a “rule” or “best practice” you should feel the freedom to break at any time).

Let’s hear it ascending and descending:

Notice how there’s an almost dreamy quality to this scale? That’s melodic minor.

I don’t use it too terribly often but hey, maybe I’ll try it out now!

What are relative minor keys?

Relative minor keys are minor keys with the same key signature as a corresponding major key.

In other words, the relative minor key of a particular major key (C major, for example) shares the same notes as that major key.

Every major key has a corresponding relative minor key. The relative minor of C major is A natural minor, the relative minor of F major is D natural minor, and so on (we’ll talk about how to find the relative minor in the next section).

Take a look at the notes in C major and A minor:

C D E F G A B

And the notes in A minor:

A B C D E F G

They’re the same! The tonic just starts on a different pitch. Now, let’s look at an easy way to find the relative minor key in any major key.

How to find relative minor and major keys

Finding the relative minor or major key of any given key is a simple process.

In fact, there are two ways to do it (three, actually, but we’ll get to the third one in a bit):

- Count back three half-steps from the tonic

- Go to the sixth degree of the major scale

That’s it!

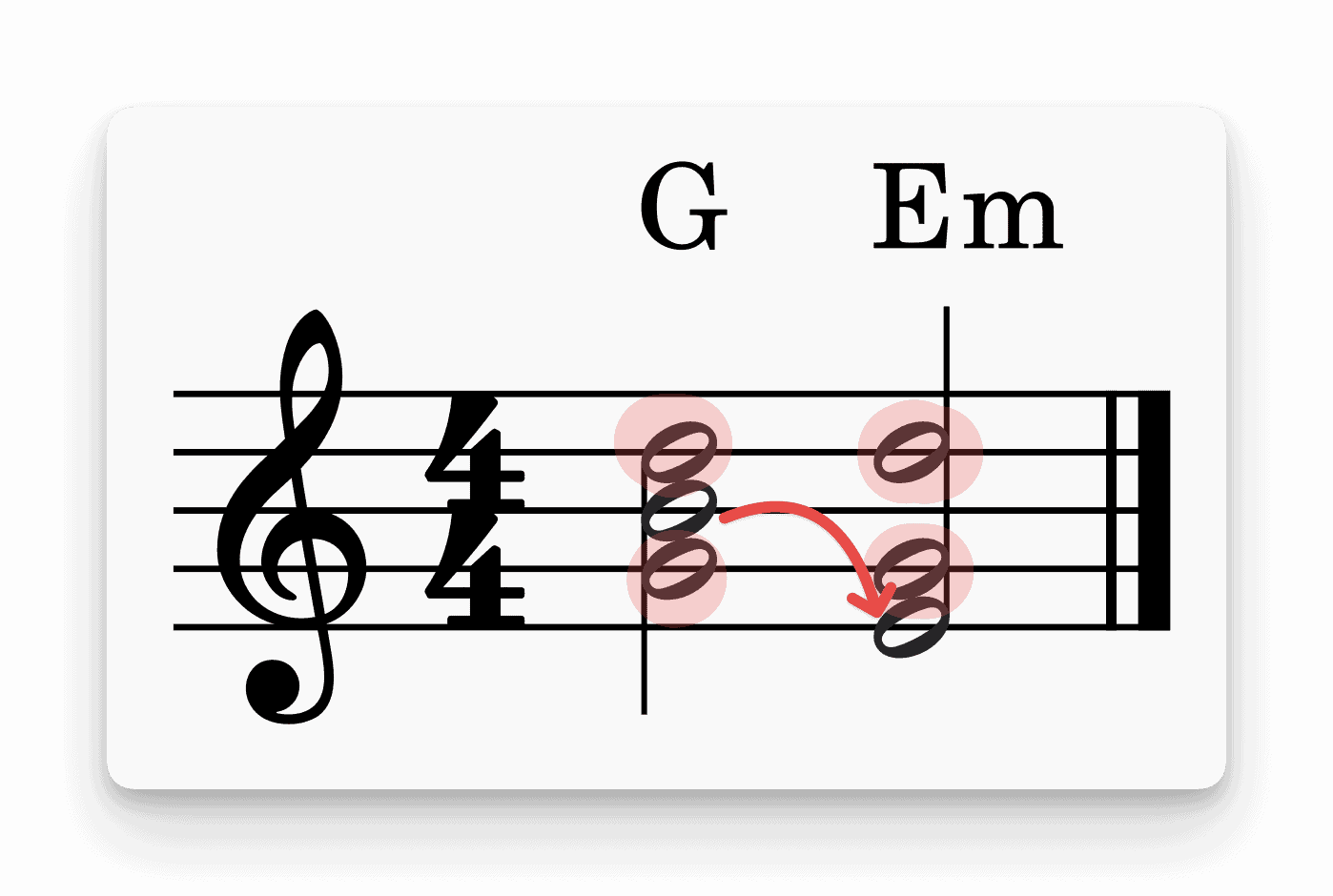

So, for example, let’s say we want to find the relative minor key/chord of G major.

If we were to count back three half-steps, that takes us from G to F#, F# to F, and F to E.

E is our relative minor key!

Likewise, if we were to count up to the sixth scale degree in the key of G major, we’ll also land on E.

In the world of music theory, the relative minor chord is the one that’s closest to the tonic chord in feeling settled or resolved. This is because the relative minor chord shares two of the three pitches with the tonic chord.

For example, G major is made up of the notes G – B – D.

If we were to simply add an E to the bottom of this chord and remove that D at the top, we’d get E – G – B.

Aka, E minor, the relative minor chord. Pretty cool!

Notice the notes in red, which are shared by both chords:

Is the key of C major the same as A minor?

So, by this logic, wouldn’t C major and its relative minor (A minor) be the same key since they share all the same notes?

Well, no.

They do share the same notes, but the difference lies in the root note: the tonic chord.

The tonic chord is the chord that most feels like home. It’s the chord that feels resolved and settled, and it’s the note that you should feel as the foundation of the song.

So even though they share all the same notes and chords, in the key of C major, we’re much more likely to feel at “home” when playing a C major chord than we are an A minor chord.

The same thing is true for any given major and its relative minor key.

To drive this point home, listen to this progression in C major:

And then this one in A minor:

Notice how even though these progressions share the same notes and many of the same chords, each feels distinctly different, with both of them feeling the most settled when they end on their respective tonic chord.

This is why C major and A minor are not the same keys, even though they share all the same notes.

Common chord progressions in minor keys

Trying to summarize all the best chord progressions in a minor key is a bit like trying to summarize all guitar music.

Where do you even begin? It’s practically half of all music dating back to the Renaissance!

Here’s a great video (once again) from David Bennett on some common minor key progressions:

Songs in minor keys

As I said earlier, minor keys are all over Western music. Here are a few tunes that are especially minor-sounding:

Pop/rock songs in minor keys:

- Californication by the Red Hot Chili Peppers

- Bad Romance by Lady Gaga

- I Write Sins Not Tragedies by Panic! At the Disco

Classical songs in minor keys:

- Moonlight Sonata by Beethoven

- Hungarian Dance No. 5 by Johannes Brahms (this is an example of a minor key tune that feels quote jovial)

- Symphony No. 5 in C minor by Beethoven (quintessential “minor key” classical piece)

Video game songs in minor keys:

- The Last of Us (main theme) by Gustavo Santaolalla (The Last of Us)

- Corridors of Time by Yasunori Mitsuda (Chrono Trigger)

- Dr. Wily Stage 1 by Manami Matsumae (Mega Man)

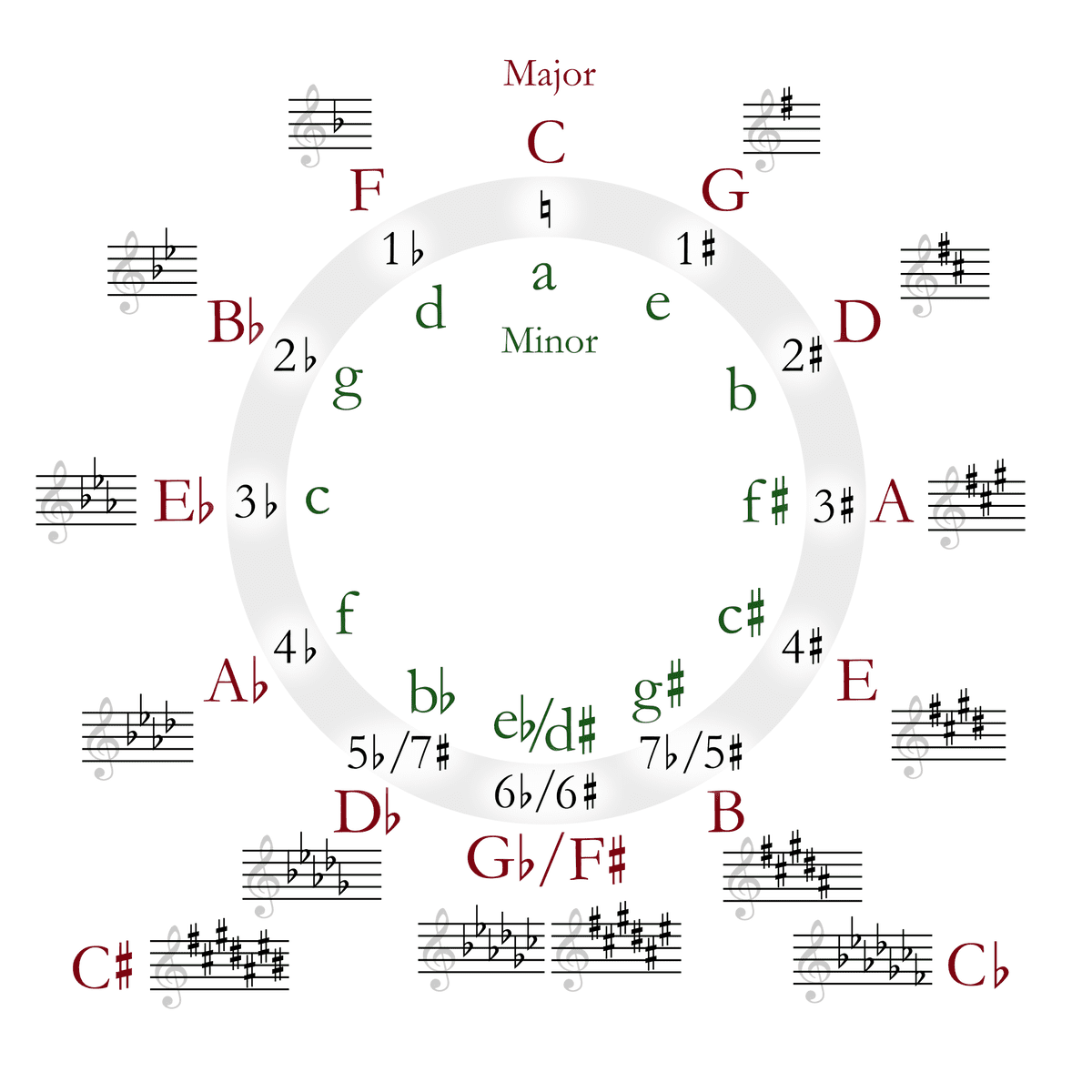

Minor keys on the circle of fifths

One of the most powerful songwriting and theory tools in existence is the circle of fifths.

We looked at it in detail in a previous post, so if the concept is new to you I’d recommend checking that out next.

And while the circle of fifths is great for understanding relationships between major keys, it’s equally useful for visualizing the relationships between minor keys.

Take a look:

Notice how the relative minor keys are below each major key in this diagram.

In addition to seeing how minor keys are related to one another, you can also use the circle of fifths to figure out relative minor/major keys.

For example, we already know that C major is the relative major of A minor, and the two are three increments apart on the circle of fifths.

Therefore, if you wanted to find the relative minor key of any major key, all you’d need to do is count three increments clockwise.

Likewise, if you wanted to find the relative major key of any minor key, all you’d need to do is count three increments counterclockwise.

FAQs about minor keys

We’ve covered a lot in this post, but you may still have questions. Here are some of the most frequently asked questions about minor keys:

Q: How many minor keys are there?

A: There are 15 total minor keys (if you count enharmonic spellings of keys). If you were to include the melodic minor and harmonic minor variations of each of those keys, that would sum to 45 minor keys in Western music.

Q: What’s the difference between a major and minor chord?

A: The defining factor of a major or minor chord is the quality (major or minor) of the third in the chord. A minor third (from the tonic) defines that key as a minor key, whereas a major third defines it as a major key.

Final thoughts on minor keys

Let’s recap everything we’ve gone over in this post.

We looked at the definition of a minor key, how to build chords in a minor key, and common chord progressions in minor keys.

Remember that a minor key is just a major key with a lowered third, sixth, and seventh scale degree.

We also looked at some variations of the typical minor scale, including the melodic minor scale and the harmonic minor scale.

We learned how to find relative major/minor keys on the circle of fifths, and we listed some examples of songs in different genres that are written in minor keys.

Here’s my challenge for you: do some critical listening of your favorite music over the next few days and see how many pieces are in a minor key.

Then, see if those pieces really sound “sad.” I think you’ll be surprised at just how dynamic, nuanced, and versatile minor keys can be in evoking a full range of emotions.

Thanks for reading, and long live the minor key!